By John Stapleton

Elisabeth Wynhausen — a battling, campaigning social justice journalist of the old school of whom in the end, despite their occasional disagreements, he had been enormously fond — was dismissed without ceremony from The Australian. Owned by Rupert Murdoch, the paper’s management style and contempt for the working journalists who filled its pages had long been a source of angst.

Like himself, Wynhausen had been fascinated by the underclass, by those to whom life had not always been so kind, and as a pioneering journalist from the days when there were few women on the city’s news floor she was tough as old boots. Her interests put her at odds with the prevailing culture of The Australian which was obsessed with catering to their AAA demographic. It was all about success, business, the triumph of the few.

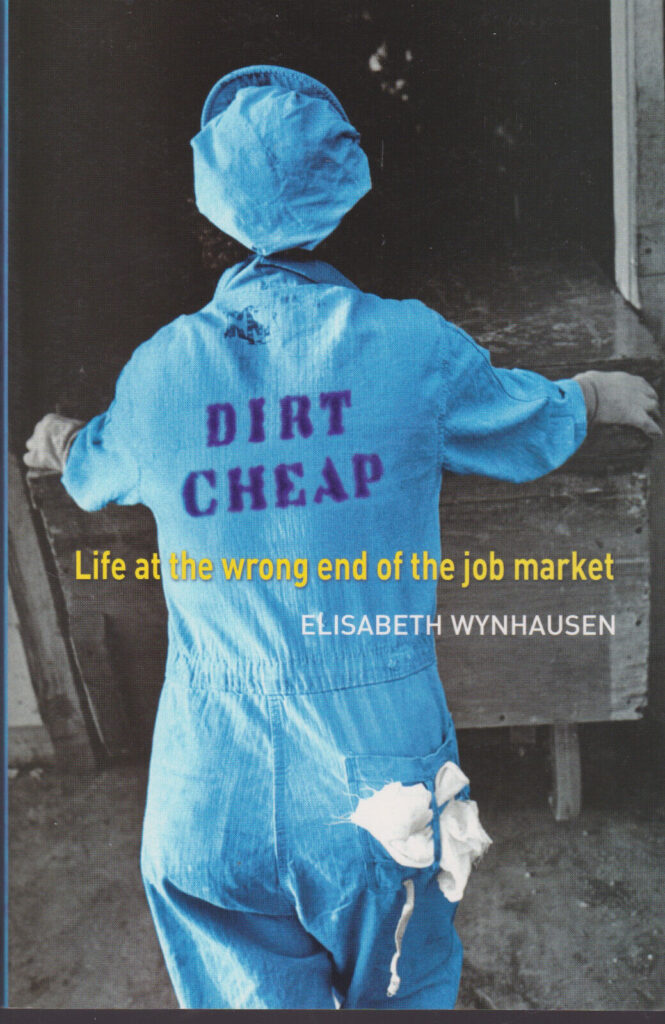

Wynhausen was the author of Dirt Cheap: Life at the Wrong End of the Job Market which was shortlisted for the NSW Premier’s Prize.

When she was fired, Editor-in-Chief Chris Mitchell, who had never written a book or been shortlisted for any literary prize, couldn’t be bothered to emerge from his office to shake her hand, bid her farewell or wish her the best for the future.

Mitchell was notorious for not deigning to speak to his journalists. It was called “managing upwards”. He managed Rupert Murdoch very well. Most of his reporters hated him.

Mitchell was notorious for not deigning to speak to his journalists. It was called “managing upwards”. He managed Rupert Murdoch very well. Most of his reporters hated him.

Wynhausen’s first book was Manly Girls, published by Penguin, a memoir of her arrival as a Jewish immigrant from Holland at the age of four and her engagement with Australia. With her typical style of disparaging humour she declared: “I’d confess to anything. It’s not in my nature to wait to be found out.”

Described as an “exuberant and engaging memoir”, as she propelled herself through one comic debacle after the other, she mused at the pedestrian eating habits of Australians: “The same scoop of mashed potato. The same subservient beans. The same lamb chop, as dried out as the Nullarbor Plains.”

Another of her books, The Short Goodbye: A Skewed History of the Last Boom and the Next Bust, published by Melbourne University Press, told the story of how ordinary Australians were affected by the global financial crisis. The work dissected the myth that Australia dodged a financial bullet by documenting the lives of those discarded on an economic minefield—from bankers to factory workers—and warned that without reform Australia could suffer a more terrible social and economic calamity from the next global rout.

Described as an “exuberant and engaging memoir”, as she propelled herself through one comic debacle after the other, she mused at the pedestrian eating habits of Australians: “The same scoop of mashed potato. The same subservient beans. The same lamb chop, as dried out as the Nullarbor Plains.”

Another of her books, The Short Goodbye: A Skewed History of the Last Boom and the Next Bust, published by Melbourne University Press, told the story of how ordinary Australians were affected by the global financial crisis. The work dissected the myth that Australia dodged a financial bullet by documenting the lives of those discarded on an economic minefield—from bankers to factory workers—and warned that without reform Australia could suffer a more terrible social and economic calamity from the next global rout.

A shorter work, also published by Melbourne University Press, On Resilience, was described as “an inspirational memoir that delves into family life and the immigrant experience”.

Prior to arriving at News Limited Elisabeth had a distinguished career working at many of the country’s leading outlets, including The Age, The Sydney Morning Herald, and The Women’s Weekly both in Sydney and in New York. She had also worked on the now defunct — but in the history of Australian journalism, significant — ground-breaking publications The Bulletin and The National Times.

This was the person the Editor-in-Chief Chris Mitchell, and thereby the newspaper itself, was treating with complete contempt.

She had been at the newspaper for the same period of time that he had, 15 years or so since the 1990s, and was one of those characters necessary for any vibrant newsroom. And while a slow writer by contemporary standards where reporters were expected to shove out three stories a day — usually stories of little consequence or regurgitated press releases — Wynhausen’s copy was deeply felt and deeply worked. It read well, broke ground.

Journalism had been in her blood and in her psyche.

As The Sydney Morning Herald described her: “Elisabeth Wynhausen could be a pain in the neck. She was raucous. She wouldn’t let up. Her default setting was full throttle. And she had an unwavering confidence that she and she alone knew how the world worked.

“But her loud mouth and sharp eyes were attached to a great heart. She had insight and was endlessly funny. Her friendships were deep. Her sympathies sound. All the restraint she lacked in life, she brought to bear on prose that was sparse and true. Her taste was impeccable.

“She was forgiven everything by her friends and a lot by her editors. Getting a story out of Wynhausen was an all-of-paper operation: endless talk and cigarettes and missed deadlines as she taste-tested each paragraph rolling slowly out of her typewriter. She ignored advice and took applause in her stride.”

Ultimately, getting her stories out was not something Mitchell was prepared to indulge.

After her peremptory, just plain rude dismissal, News Limited protocol was that she should have emptied her desk, been escorted out of the building and not allowed back in.

Wynhausen ignored them. No one had the heart or the gumption to sick the security guards onto her.

Throughout that final day a gutless Mitchell stayed cowering in his office; not emerging to say goodbye, to apologise or express regret at the circumstances which had led to her departure, to thank someone for her years of service.

Mitchell knew the news floor hated him. He didn’t care. He still got paid his sterling salary for doing bugger all no matter how much he decimated the paper’s personnel, or what fake economic or managerial justification there was for the latest round of sackings. He is also a coward and a bully.

The old man had seen it all before — time after time after time — on Sydney’s news floors.

Sooner or later, he knew perfectly well, he too would become the victim of the same pogroms that had destroyed so many other talents and careers.

It didn’t matter how many years you had served The Great Rupert or his henchman Mitchell. You were instantly dispensable.

The newspapers paid in their discernible lack of character or depth. And the nation as a whole paid because its major newspaper became so callow, so shallow.

After they had both left the paper, although rarely in Australia at that point, he would serendipitously run into her in odd places: walking along Bondi Beach, in the Blue Mountains. She seemed lonely, lively, still full of ideas, curious takes and opinions on just about everything, but lost.

Wynhausen could not live, could barely breathe, outside newspapers. It wasn’t long before she curled up and died, keeping, until the final days, news of her illness secret from even her closest friends.

Back in Australia in 2013, he had been saddened by news of her death and went to her funeral which was attended by many of the city’s best known journalists.

Mitchell did not even bother to accord her the basic courtesy of attending. Or perhaps he knew he would not be welcomed.

Only days after her death, conservative alter boy Tony Abbott became Prime Minister.

The standard joke, even at the funeral, was that she simply couldn’t stand the thought of living in a country run by Tony Abbott.

She would have been in a fury, if not of litigation, of a determination to make his Prime Ministership as miserable as possible.

As it turned out, in the years that followed Australia lurched ever further to the right, into a totalitarian mindset which would have appalled her; as the people of Australia were utterly betrayed by their political class, both left and right.

Not just a pioneer in her day, Elisabeth was one of the last crusaders of a style of journalism which she believed could effect societal change, and make the world a better place.

Journalism became entertainment, social change became a rigor mortis grin of diversity apparatchiks, and Australia, and Australian journalism, was a sadder place without her.

Only days after her death, conservative alter boy Tony Abbott became Prime Minister.

The standard joke, even at the funeral, was that she simply couldn’t stand the thought of living in a country run by Tony Abbott.

She would have been in a fury, if not of litigation, of a determination to make his Prime Ministership as miserable as possible.

As it turned out, in the years that followed Australia lurched ever further to the right, into a totalitarian mindset which would have appalled her; as the people of Australia were utterly betrayed by their political class, both left and right.

Not just a pioneer in her day, Elisabeth was one of the last crusaders of a style of journalism which she believed could effect societal change, and make the world a better place.

Journalism became entertainment, social change became a rigor mortis grin of diversity apparatchiks, and Australia, and Australian journalism, was a sadder place without her.

http://elisabethwynhausen.com/