Agent Orange clean-up, 37 years on

Abstract

Original copy:

John Stapleton

Americans have been astonished by this week’s announcement that the

lingering impacts of the infamous herbicide Agent Orange are only now

to be addressed, 37 years after the end of the Vietnam War.

The historic $450 million amelioration efforts to destroy the

chemicals remaining in the environment and treat those suffering from

disabilities begins on Thursday of this week

at Vietnam’s worst affected site – the former American military base

and now bustling airport of Da Nang.

Until 2008, when the heaviest concentrations of dioxin at the airport

were concreted over and advisory notices issued to the community,

people were swimming and fishing in a poisoned lake adjoining the

airport.

The painful story of neglect and obfuscation surrounding the impacts

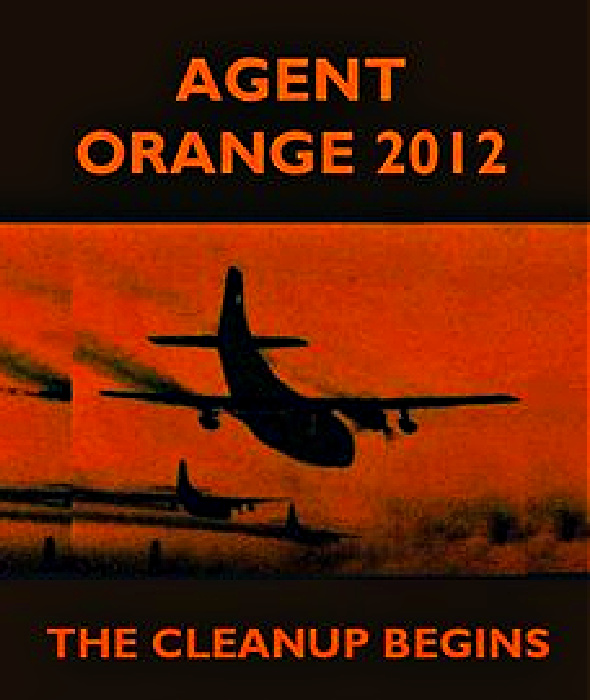

of the herbicide Agent Orange begins in 1961. As part of its military

operations, in that year the US government ran its first experiments

destroying forests and crops. Over the next decade more than 43

million litres of Agent Orange was sprayed at up to 50 times the

manufacturer’s recommended levels across 24 percent of southern

Vietnam, including across thousands of villages.

This week marks the first effort by the American and Vietnamese

governments, along with private groups including the Ford and Aspen

Foundations, to address the problem.

The triumph to be seen at the airport this week involves the digging

up of 77,400 cubic metres of soil which will then be heated to a

temperature of 300 degrees centigrade and repeatedly tested until

dioxin levels are at zero and then re-interred.

The historic event owes much to the efforts of one man, the

distinguished Dr Charles Bailey. His arrival in Hanoi as head of the

Ford Foundations regional operations in 1997 and his personal shock at

the ignorance and lack of action over Agent Orange marked the turning

point from hand wringing this week’s ground breaking efforts.

Surveys funded by the Ford Foundation and the Aspen Institute found that although extensive land

areas had been sprayed, none of the chemical remained. Agent Orange

breaks down within a matter of days or weeks.

The problem arises with what Dr Bailey calls a “manufacturing defect”,

the existence of a chemical known dioxin associated with the

herbicide. Manufacturers did not realize that if the Agent Orange was

not “cooked” at an exact temperature, the unintended consequence was a

chemical which does not exist in nature and is one of the most

poisonous substances ever created.

The maximum allowed level for dioxin in human blood is 7-8 parts per trillion, i.e. equivalent to 7-8 molecules of water in an Olympic sized swimming pool.

“If Agent Orange was just a herbicide, it would have destroyed the

vegetation but there wouldn’t have been the direct and lingering

impacts on US and Vietnamese soldiers. Those affected, often living

around former American military bases, have shorter life spans and a

greater chance of their children having birth defects.

“Dioxin wasn’t invented, it wasn’t wanted, it was an accidental contaminant.”

After investigation of the 2,735 former American military basis

studies identified 28 hotspots across Vietnam, all of them sites where

the chemical had been mixed before being loaded onto cargo planes for

aerial spraying.

The three most severely affected centres are Da Nang, Bien Hoa east of

Ho Chi Minh and the coastal city of Qui Nhon, all heavily populated.

Dr Berrie says unlike many vaguely focused international projects,

Agent Orange is a humanitarian story with a beginning, middle and end.

“For Congress $450 million is virtually a budgetary rounding figure,”

he says. “I was taught as a child to clean up my own mess. We did not

intend to create this problem but we have a responsibility as a nation

to fix it. To do so is good for America, Vietnam and the bilateral

relationship.”