By John Stapleton

The Anthropocene Project is a multidisciplinary body of work by photographer Edward Burtynsky, filmmaker Jennifer Baichwal and cinematographer Nicholas de Pencier.

The project’s starting point is the research of the Anthropocene Working Group, an international body of scientists who argue that the Holocene epoch ended around 1950, and that we have officially entered the Anthropocene, an unprecedented moment in planetary history.

Humans now arguably change the Earth and its processes more than all other natural forces combined.

The Anthropocene Project fuses photography, film, virtual reality, augmented reality, and research, resulting in a body of work that attempts to give audiences a panoramic view of the Anthropocene.

The project, currently on view at the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Ontario, will travel to Italy early next year.

It includes a just released book, a major travelling museum exhibition, a feature-length documentary film to be premiered at the 2019 Sundance Film Festival, and an interactive educational website.

Below is an extract from the Edward Burtynsky’s essay Life in the Anthropocene, as it appears in in the art book Anthropocene.

If we destroy nature, we destroy ourselves.

All images are © Edward Burtynsky and courtesy of the Nicholad Metivier Gallery, Toronto. They are not for reuse without permission.

Burtynsky’s office can be contacted through his website.

The Impact of a Single Species: Us

North Rhine, Westphalia, Germany, 2015

My earliest understanding of deep time and our relationship to the geological history of the planet came from my passion for being in nature.

As a teenager I loved to go on fishing trips, canoeing along the pristine isolated waterways of Ontario’s Haliburton Highlands. That experience of wilderness left an enduring mark that still informs my response to landscape.

I came to appreciate a state that exists without human intervention or disruption.

I can remember learning, for example, that 12,000 years earlier, in place of the lakes and trees where I cast my lures, a solid sheet of ice three kilometres-thick had once covered the land.

I realized that it was not only these wild places, but the planet as a whole that is, and always will be, a dynamic, ever-changing system.

Our planet has borne witness to five great extinction events, and these have been prompted by a variety of causes: a colossal meteor impact, massive volcanic eruptions, and oceanic cyanobacteria activity that generated a deadly toxicity in the atmosphere.

These were the naturally occurring phenomena governing life’s ebb and flow.

Now it is becoming clear that humankind, with its population explosion, industry, and technology, has in a very short period of time also become an agent of immense global change.

Arguably, we are on the cusp of becoming (if we are not already) the perpetrators of a sixth major extinction event.

Our planetary system is affected by a magnitude of force as powerful as any naturally occurring global catastrophe, but one caused solely by the activity of a single species: us.

Insatiable Human Striving

Berezniki, Russia, 2017

In the cavernous potash mines beneath Berezniki, Russia, I was challenged by utter darkness, only to then experience the amazing psychedelic patterns and colours of the walls, not revealed until they were captured by our LED lighting techniques.

With my colleagues walking the mobile lights up and down the tunnels, literally painting the mineral-laden walls with light while I took the pictures, we were able to create myriad images that could later be joined together, compressing our collective time-based experience into static form.

This mine, one of five that I photographed in Siberia, comprises an estimated 3,000 kilometres of tunnel.

Between 1900 and 2000, the increase in world population was three times greater than during the entire previous history of humankind — a quadruple increase from 1.5 to 6.1 billion people in just one hundred years.

Even in the brief span of my own lifetime, the Earth’s population has more than doubled to 7.2 billion.

This phenomenal growth has coincided with a period of great scientific, cultural and economic achievement, a deeper understanding of who we are, what we are capable of, and our relationship to the universe.

However, as we access an ever increasing body of knowledge with ever-increasing speed, we are also becoming more aware that this progress provokes as many pressing questions as it provides answers, with countless more people living in abject poverty and helplessness than those few with seemingly unassailable comfort, wealth and power.

This extreme polarization has perhaps always been inevitable in the course of human evolution, the result of our species’ innate social predisposition to greed.

Unlike other species, there seems to be no end to our quest for food, comfort, shelter, sex — the fundamental necessities of survival that are now pursued in overdrive, far beyond our existential needs.

But with this insatiable human striving has come our assault on the very planet that sustains us.

During the last century, the use of global materials increased eightfold. Humanity currently uses almost 60 billion tons (Gt) of material annually: biomass, fossil energy carriers, metal ores, industrial minerals and construction minerals.

It’s clear that the expanding industrial metabolism is a major driver of global environmental change.

I have come to think of my preoccupation with the Anthropocene — the indelible marks left by humankind on the geological face of our planet — as a conceptual extension of my first and most fundamental interests as a photographer.

Freeing the Lens

I’ve always been concerned with showing how we affect the Earth in a big way. To this end, I seek out and photograph large-scale systems that leave lasting marks.

At the heart of my challenge has been the pursuit of vantage points that best enable me to picture the relationship of these systems to the land.

From my earliest shooting trips in the 1980s, I always sought to free my lens from ground level. In the early work on railcuts, homesteads, quarries, mines and shipbreaking yards, I tried to find elevated spots to plant my tripod: a berm, a bridge, a rooftop or overpass; a perch that offered sweeping overviews of the subject matter.

For my China and Oil projects I rented mobile scissor-lifts and bucket-lift trucks, raising myself up from the earthbound vantage points of my earlier work, taking in the wider spectacle.

Lagos, Nigeria, 2016

The year 2006, however, marked a major change towards digital technology and a new way of generating work. I could now mount and electronically control my camera from a 40-foot pneumatic monopod.

By using drones, airplanes, and helicopters, I could also achieve a bird’s-eye perspective, rendering subjects such as transportation networks, mining, agriculture and industrial infrastructure more expansively, capturing vistas that had eluded me until then. Rather than having my work be dictated by the limitations of topography or man-made structures, my lens could now literally fly.

In recent years, digital camera technology has become my main tool, allowing me to explore extended lens-based approaches.

For The Anthropocene Project, large high-resolution murals measuring up to 12 by 24 feet are now made possible through capturing multiple frames and then seamlessly ‘stitching’ them together, using software to create enormous printing files.

Such has been the method behind several mural-size images I have recently made documenting extraordinary places: from the urban sprawl of Lagos and the Carrara marble quarries to the lush, primal forests of British Columbia and the coral reefs in Komodo National Park, Indonesia.

Infinite Possibility Infinite Foreboding

[While producing a recent series on Oil Bunkering in the Niger Delta I found] myself confronted by some of the most foreboding landscapes I have ever seen.

It’s not since making my work on the Sudbury nickel tailings in 1996 that I had felt quite the chill of emotions that such an utterly devastated landscape can produce.

[The Internet has become] an invaluable tool, enabling my extensive location research but also allowing me to view and capture subjects from even greater distances.

Using high-resolution satellite imaging, I have begun making compositions that extend my earlier interest in agriculture and its geometric interventions in the landscape.

Extending the lens even further by using specialized 3D software, I am now able to capture and stitch together thousands of images of an object, or a place, and render such scenes in full detail — as images that may be experienced in all their dimensionality.

This has reignited my interest in looking at picture-making as a form of sculpture — something I experimented with, albeit more crudely, more than two decades ago.

I continue to be challenged by my practice, learning about technique, and also about the world around me. The work always leads me to new understandings, and new ways of perceiving.

Each place has its own story to tell, and its own distinctive impact.

Cumulative Impact

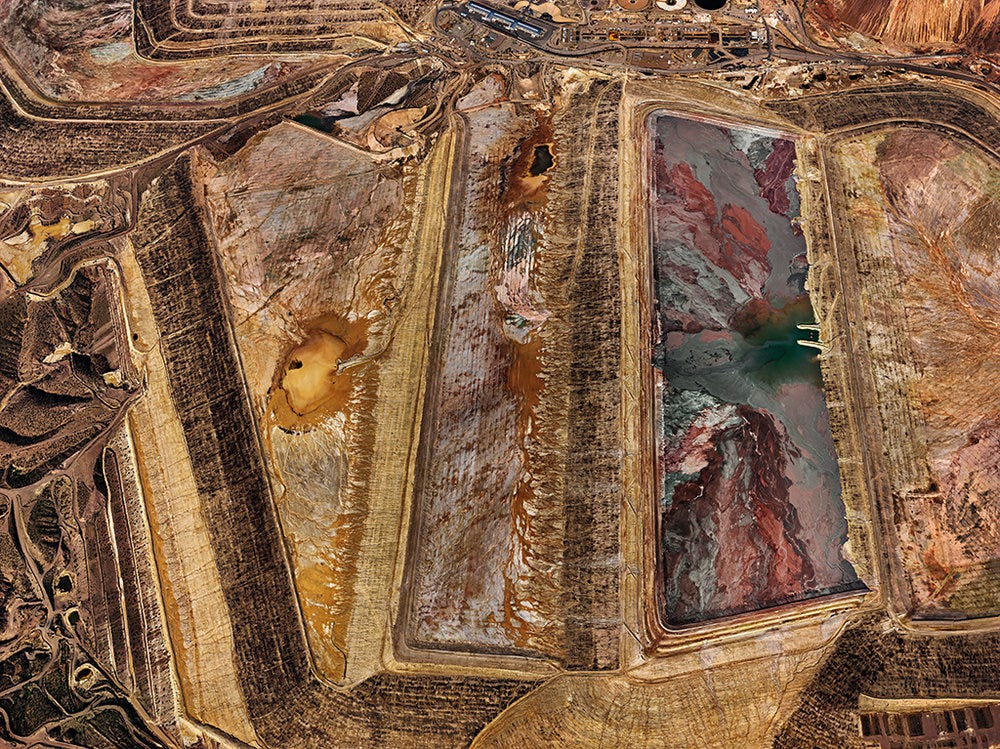

Silver City, New Mexico, USA, 2012

Beauty spurs me on to ever more experimental ways of bearing witness.

As a collaborative group, Jennifer, Nick and I believe that an experiential, immersive engagement with our work can shift the consciousness of those who engage with it, helping to nurture a growing environmental debate.

We hope to bring our audience to an awareness of the normally unseen result of civilization’s cumulative impact upon the planet. This is what propels us to continue making the work.

We feel that by describing the problem vividly, by being revelatory and not accusatory, we can help spur a broader conversation about viable solutions. We hope that, through our contribution, today’s generation will be inspired to carry the momentum of this discussion forward, so that succeeding generations may continue to experience the wonder and magic of what life, and living on Earth, has to offer.