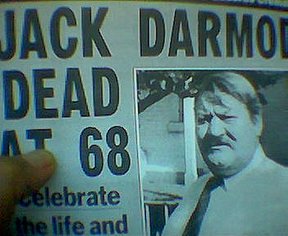

It was Jack Darmody’s funeral today. He got a good roll up. Jack was a legend of Australian journalism from the 1960s, 70s and 80s, when he worked as a police reporter on some of the country’s leading tabloids, including the now defunct Daily Mirror in Sydney and The Truth in Melbourne. He broke the story on the Great Train Robber Ronald Biggs hiding out in Australia, arriving at the house where Biggs had been hiding only minutes after Biggs had fled, well ahead of the cops.

Jack was of the old school, when journalists were expected to be drunks and misfits, not the cleancut tertiary educated mob of today. At endless press conferences the young ones are more likely to drink mineral water; in Jack’s day if you didn’t feel like a beer it was only because you wanted a scotch. He died in St Vincent’s Hospital’s Sacred Heart Hospice with a flask of rum beside his bed. Their services to the dying, and after all these years of Aids their good humoured tolerance and loving care of the eccentrics who choose this inner-city hospice, are nothing short of excellent.

If not kind to himself, Jack was often kind to others, and was popular amongst generations of cadet journalists for the world that he showed them. Jack would never last in the present clime. He would have been sacked for being drunk long ago.

In amidst the heavy drinking legend, Jack left a trail of ex-wives and broken relationships. I watched the sad face of his son; who no doubt had had a hard time of it all. Jack was known across the pubs of Sydney, for a long time where he lived at the Darlo Bar, in Darlinghurst, in more recent times, after he had fallen and ended in a wheelchair. Housing found him a place where he could get in and out, but it was at Ultimo, on the perimeter of his natural drinking grounds. He was always at the bar early, smoking unfiltered camels, sipping scotch. He had at once a melancholy and jovial air; always good company if nothing else, always happy to catch up on gossip or rail against the present incumbents of power.

Jack never had any intention of stopping drinking. The rest of us might bounce in and out of detoxes or seek help in twelve-step programs, AA, NA or PA, pills anonymous, was the usual range. In eighties Sydney these groups were the height of fashion; even things like Co-dependents anonymous. Or perhaps a group for those who had become addicted to twelve step programs. It reached a farcical stage. But none of this, of course, was for Jack. As sports writer Peter Kogoy said in his eulogy, quoting Walt Whitman: “I am large, I contain multitudes”. The line summed Jack up perfectly . He was bigger than himself, larger than life. Or as one barmaid who went to his funeral, a woman who had spent many hours alone with him in the Darlo noted; “Of all the many barflies I have known, he was the one with the most perceptive intellect.”

I remember particularly with Jack one day during the 1980s, after he had finished work as a police roundsman and the decades long war between the city’s tabloids, The Mirror and The Sun, had finished with the papers being shut down. I was working as a reporter at the Sydney Morning Herald, and he had for some reason latched on to me as someone who might be sympathetic to the story he was flogging. He was himself an old boxer – as a young amateur he had been known as the The Mooretown Mauler, or whatever the name of the Melbourne suburb was from whence he then hailed; there was a picture of him as a strapping, fit, handsome young fighter kitted out and ready for a brawl, on the brochure that was passed around at the pub. There was, basically, no resemblance between the young man in boxing gloves and the old man who died.

Needless to say, a somewhat different approach now applies from the army of modern PR women. When I tried to refuse a drink, Jack wouldn’t take no for an answer. As far as he was concerned, “I’m working” was simply not an excuse not to to drink. He had one of those faces, it just seemed to take up the whole room.

At the time, in the eighties, the Liberal government of the day, or at least its Housing Department, had decided for whatever reason to cut the funding for the boxing ring on the housing estate. It had been a place, no such places exist anymore, where young men worked out, trained to be boxers, got their angst out in sound and sweat, got a bit of exercise, gave them a chance to hang with their mates, to prove themselves, or more commonly, just learnt to defend themsleves in tough neighbourhoods. The boxing gym, unrenovated and unpainted, had been very important to the troubled young lives of the boys who grew up on the estate; their parents drunk, deformed, derelict or dead.

It was not just a working class tradition, but a male working class tradition, and as such was completely out of fashion with the leftwing bureaucrats who’s own agendas bore almost no resemblance to the concerns of the working classes they supposedly represented. The first thing Jack tried to do was get a can of beer in the hands of myself and the photographer. His idea of PR was to buy as much alcohol as he could and pour it down the gullets of as many journalists as he could. He had a big green garbage bucket full of ice and beer, with several cartons stashed conspicuously to the side. But as a glorious sign of just how good these days were, two full bottles of scotch also floated in the ice. It was late in the day, about four o’clock, with some of the kids starting to come in from after school, the place large and poorly lit, the smell of sweat. In the ring, an aboriginal boxer of some local renown was warming up. Jack was clearly going to be still there at midnight, drinking and holding court and waging the good fight against the bureaucrats and politicians and arse-wipes in government, many of whom he had already rung to point out the heartlessness of their destruction of this working class gym.

Well the photographs were beautiful and the story got a run. Unlike the cool PR princesses of today, Jack rang up the next day and was fulsome in his thanks. John Fahey was Premier at the time, and from memory, as Jack told me, he had taken one look at the story, stepped in and fixed the problem, not just reversing the bureaucrat’s indifferent brutality, but had given the gym extra money and resources to ensure its survival.

MEDIA WATCH:

A number of reports remembered Jack fondly:

Mark Morri wrote in part:

As a storyteller he could write and tell a yarn with the best of them. He could be poignant, witty or straight-to-the-point with a simplicity that could be brutal. But it’s more the stories about Jack Darmody,rather than by Jack Darmody, that he will be remembered for. A big man physically, he could fill a bar with his laughter or empty it just as quickly with a growl. To make him laugh was a joy. To make him angry was akin to a death sentence. Many a cadet reporter learnt more about journalism — and life — from Darmody in the Shakespeare Hotel than in a newsroom. I count myself lucky to have been one of them. Darmody would sit in the corner, eyes on the door “just in case”.

As a trained observer and judge of character, he was unmatched and he’d sum people up in an instant — sometimes to their intense discomfort. Like the armed hold-up squad detective I introduced him toone day. It was a short introduction. Darmody looked him up and down and snarled. After the detective left, which was pretty quickly, Jack looked at me and grunted.“He’s crooked,” he said. “Who?” I asked.“Your new mate,” Darmody said.“How could you know that? You hardly said two words to him,” I said.“Brand new Italian leather shoes, fifty bucks each way. He’s crooked. ”A couple of years later that same copper was sent to jail for taking bribes from a drug dealer.

Darmody didn’t chase fame, just a story or mate who needed help. He fought for those doing it tough. For years he and best mate John McColl would try to teach boxing — and maybe some manners — to street kids at Glebe Gym. It was in a Glebe early opener one morning I asked him if he wasn’t worried about the toll that drinking 15 schooners, a dozen rums and smoking 80 Camel a day was having on his health. He replied: “I’m 48, I’ve been married three times, once for a week. I have done two tours of Vietnam. I know prime ministers and murderers by their first names. If I go tomorrow, I think I’ve done enough.”

Mark Day wrote in part:

Jack is a reporters’ reporter if ever there was one, up there with the best of our times. He’s in Sydney’s St Vincent’s hospice fighting a long battle with that pernicious beast, cancer.

He is as tough as teak and as soft as butter. The cancer must have found his soft side because he would have belted the hell out of it had it been stupid enough to try to meet him head on. Built like aside of beef, he was a boxing champion in his youth and he knew his way around a ring before he knew life on the other side of the ropes. His appearance could be highly intimidating if he wanted to convey the message that he was not to be trifled with — a man mountain given to scowls, gravel-voiced growls, and body language reminiscent of a bullpawing the ground before charging. But it was mostly an act. He preferred to use words as his fists and he was very handy at it. He wrote like a poet, always on the side of the angels; always in search of dignity for those who had precious little of it.

Not everyone got it with Jack. They saw a barrel-shaped man, utterly devoid of dress sense, with rarely-combed hair and endless Camel cigarettes poking out from a singed but formidable moustache; they heard him demand the facts, the truth, or just the story, and they registered rejection, puzzlement or fear. But those who knew him –particularly women — found a kind, caring man who would shift heaven and earth to help and protect them. His body had to be so big to hold his heart.