Everything came in torrents from the past; always disturbed, always flung to the four winds, good times non-existent.

The world had become a flat, monochromatic place, leaden grey, terrifying. There was no coherent, single personality. The grey was all that I knew, all it seemed I had known for years. Comfort came from the familiarity of despairing routines. If I sought wealth, it was purely to fritter it away. I had no belief in a brighter future.

On the outside I was a cheerful, entertaining character. “A Cutter”, as they are called in Australian parlance.

People would comment on how relaxed and easy going I was, how I knew everybody, could talk to anybody.

Inside a cringing, sad person had evolved over many years. I wore this melancholic view of the world like a cloak; leaves blown on soggy ground, swirls of dark colours, orange sludge, despair, a kind of existential futility, etched into the ravishing landscapes I always sought.

I wandered into a job at The Sydney Morning Herald, then regarded as one of the world’s top 20 newspapers, out of these doom laden winds with no ambition, no hope of a career, just a sad determination to see out promises made to myself a long time ago.

I would live or die by the typewriter.

By the time I did actually arrive on the doorsteps, or loading docks, of The Sydney Morning Herald, through a ragged series of events after the collapse of a long term relationship, I didn’t, in my heart of hearts, believe my determination to live or die as a writer would actually succeed.

Through A Glass Darkly

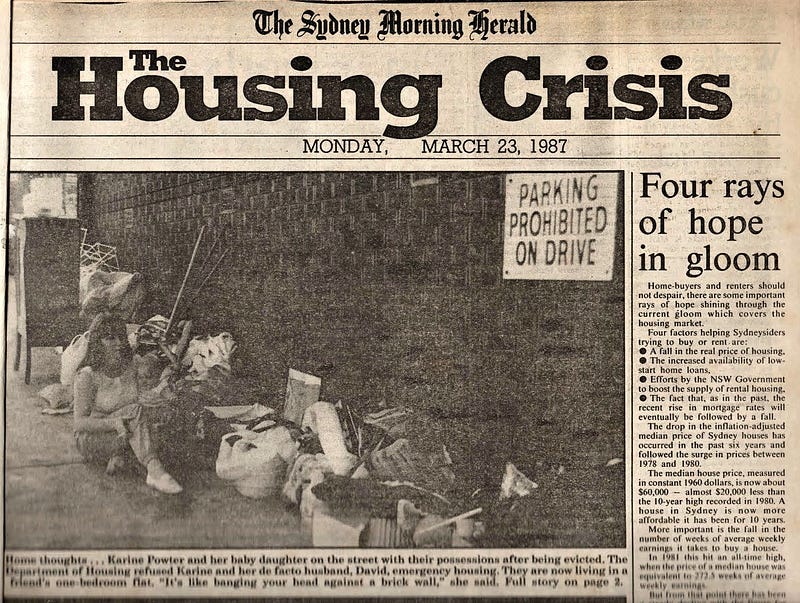

A friend who was working as a housing officer for people on welfare, Cara MacDougal, helped fuel me with enough social justice stories to attract attention. Her support made all the difference.

At the time I was taking my own photographs. One in particular that got a good run was of a single mother who had just been evicted from her home. In the chaos of eviction, her children’s possessions were strewn down the narrow concrete walks of their bleak apartment blocks.

Even I could make a litter of toys evocative.

The homeless stories, which were influential in getting the staff job at The Sydney Morning Herald, weren’t the beginning and the end, as I might once have thought.

Most young journalists come on to newspapers and magazines, and these days blog sites and online news outlets, with their heads full of idealism and a string of story ideas to back it up.

But newspapers burn stories like a bonfire; and soon enough you’ve written or turned into news stories all your social justice obsessions.

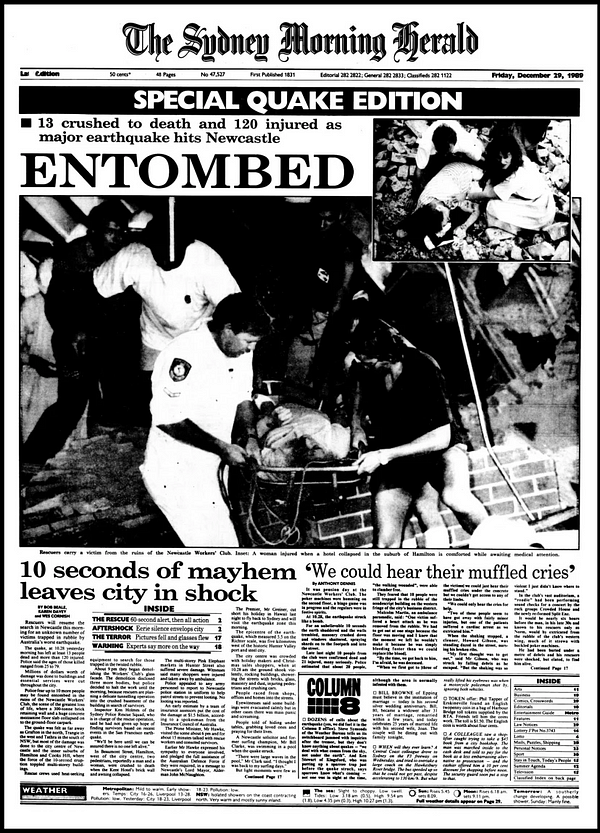

And then you have to move on; and assume instead the honoured role of observer, recording the multiple stories of the mayhem and intrigue of the world around you.

The Honoured Role of Observer

Did those photographs of the homeless, their belongings scattered on the medium strip outside a grim block of apartments really change anything? Encourage governments to take a more compassionate view?

The stories certainly didn’t help the actual people involved, although at the time, unused to the transient impact of sob stories, I thought that by bringing the multiple injustices of their plights to light I was doing them a great favour.

Somehow, out of sheer persistence and the kindness of strangers, I began to get stories published in the city’s finest newspaper.

Although I had spent several months perfecting the art of the swan dive as part of another drink sodden downward spiral, in my first approaches to The Sydney Morning Herald I used an old and often surprisingly successful line, “I’ve just got back from overseas and I’m looking for work”.

On the path, several people went way out of their way to help me.

Just as in former years when an editor on the Review section of The Australian Financial Review, Judith Hoare, painstakingly taught me how to write for newspapers, so this time round one of the editor of the Saturday feature section of The Sydney Morning Herald, took me under his wing.

Whatever the reason Thomas Liddle, after giving me a string of demanding feature assignments, took it on himself to recommend me to the editors.

And thus I began to do my first casual news reporting shifts for the best newspaper in the country.

In its power, status and hold on the city’s imagination, the paper was a revered institution without peer.

It’s hard to imagine now, when newspapers are no longer admired as bastions of truth representing the highest ideals of a community, just how admired and how celebrated The Sydney Morning Herald was.

In the lists of such things, it was regularly ranked as one of the best newspapers in the world.

Just getting a letter into the letters page of The Sydney Morning Herald was a major feat. Much less being one of their reporters.

Adjusting to the mainstream took some doing

For a start, from a practical point of view, it was barely possible to decipher the hieroglyphics I left behind.

The snail trails of discordant, disconnected, images made sense to almost no one. I had been a long time out there.

I had to take detailed notes on every situation just to make certain of getting it right. The door was blue. The ceiling grey. He had a moustache. She blonde hair. The children were three, five and ten. The car maroon.

The sun was setting as the ambulance arrived. Burnt trees formed skeletons against the darkening sky. The wooden house was once painted white. A ramshackle fence enclosed daisies growing wild in a neglected garden.

Everything, I took it all down, filling out note pad after note pad.

Back in the office I would regurgitate too much, struggling to confine the story to the standard 600 words.

Back then, when we were out on assignment in the news cars, the journalist was expected to be the boss and the driver and photographer to follow their lead.

In a later era there would no greater offence than to refer to “my photographer” or “my driver”.

The first time I had to radio into the news desk I didn’t know which button to press on the microphone; and my inexperience was painfully obvious.

My amateurishness didn’t last.

It was my preparedness to work Sundays that finally unlocked the door to the mainstream.

At that stage of life, disoriented and sad following the break-up of a long term relationship, there weren’t any squabbling children or longing boyfriends at home, no picnics with friends. My arms were bruised and the flat mates barely tolerated my behaviour. I had won and lost so many times, I felt even older than I had felt as a child.

I didn’t much care how I spent the days.

Sooner or later the paper’s hierarchy noticed that I kept getting a run on Mondays, the paper wasn’t getting sued and the stories weren’t too badly written. For months, poverty stricken and attempting to stabilise my life, I kept up the casual shifts.

Page Zed

My first front page would never normally have made it to Page Zed, much less the front. In those days, prior to so much advertising drifting to the internet, there were always a lot of news pages to fill and a scrabbling desperation by the editors to get enough stories for the next day.

In a medium sized city like Sydney, there wasn’t always that much newsworthy going on.

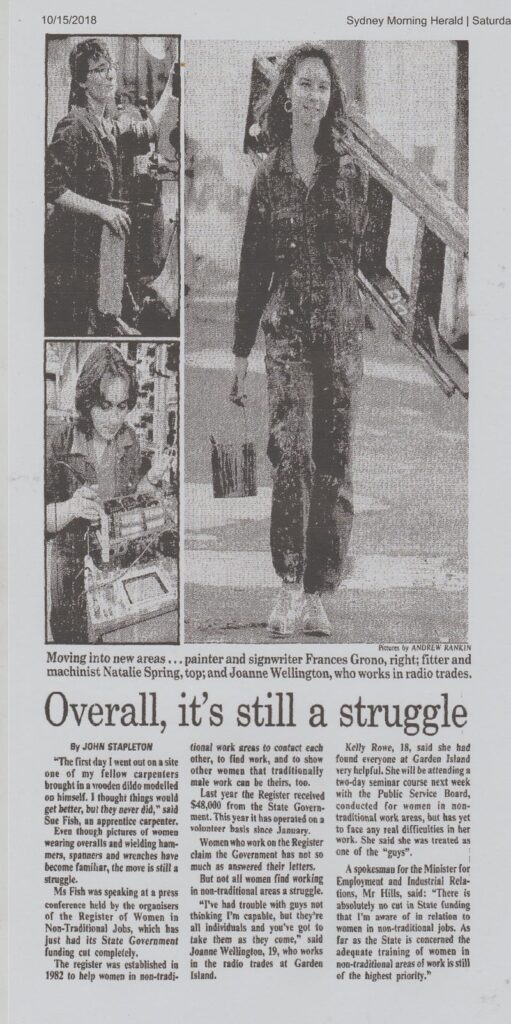

“There’s a register for women in unorthodox jobs,” the Chief of Staff said. “Their funding has run out and they’re whinging for more. These people always want more taxpayer’s money, they can’t possibly stand on their own two feet.

“Anyway, we’re desperate for pic stories tomorrow, see what you can get. Try and find some cute young woman carpenter, covered in saw dust, or a mechanic, grease streaking her face, dribbling down her breasts. Just make sure they’re cute, we don’t want some bull dyke.”

So I headed off to the meeting in inner-city Surry Hills with the most foul-mouthed of all the SMH photographers. Like an early Chef Ramsay, he found it impossible to utter a single sentence without using the “f” word.

We were late, as the SMH of those days almost invariably was, a sense of the urgency of news yet to overtake the venerable institution.

The room was full of the righteous anger of 300 or more women crammed into a tiny space.

Eventually the woman allocated to take care of the media — we were the only media outlet which had shown up — cleared a spot for us.

We were, after all, The Sydney Morning Herald.

We sat cross-legged on the floor; completely surrounded, the only men. The 1980s was the peak of male-bashing feminism, of women’s collectives, power suits and committed separatists, of serious debate about whether all men were rapists and bashers, whether lipstick was self-repression or true liberation could be achieved without the elimination of all men from women’s lives.

I tried to feel comfortable, nothing to it, I’m a progressive kind of guy, go girls, all of that. I had done Women’s Studies at university in the 1970s.

I thought of myself as a SNAG, a Sensitive New Age Guy, at the cutting edge of gender transformation.

Speaker after speaker portrayed the government’s failure to continue to fund the directory of women in unorthodox jobs as not just a slight against all working women, but yet another blow by a patriarchy determined to keep the sisters in the kitchen.

“There’s no f’n picture here,” the photographer whispered, loud enough for a dozen of the sisterhood to overhear.

“Just look at them. None of them make a f’n picture mate. I’m out of here. I’m going to find something else.”

“I’ve got to stay and listen,” I whispered back.

“Well I don’t, I’m f’n gone,” he said, standing up and elbowing his way through the crowd of hostile women.

I sat there, very uncomfortably, knowing full well the women around me had heard every last word the photographer had said.

As representatives of The Sydney Morning Herald we were one of their only chances to get any mainstream media attention and thereby put any pressure at all on the government and to thereby save their project. They had to bide their tongues.

On and on the speakers went. By the time I got back to the office that day I had interviewed a woman carpenter, plumber and electrician as well as the organisers. I wrote up the story on the antiquated computer system, made it as interesting as possible, assuming as my fingers rattled across the keyboard that it would never get a run.

The subject might have been important to the people involved, but a directory of women in unorthodox jobs wasn’t earth shattering. Journalists were always being targeted by groups whose funding has run out — noble cause after noble cause.

Next day the story was on the front page, my very first front page story.

It was the picture that did it

I learnt forever the value of a good photograph in dragging a story onto the front; or higher in the “book” as the sections were called.

But that day a large photograph, run wide and deep, of a drop-dead gorgeous young woman adorned the front page of The Sydney Morning Herald.

She was carrying a ladder, with the Opera House in the background, her white overalls stained delicately with paint. The upper flaps of her overalls were just loose enough to provoke the imagination of males around the city. “Can I help you carry that?” a hundred thousand voices asked as their minds licked off the delicate traces of labor, the glorious smell of sweat.

I never got a thank you from the organisers of the Women in Unorthodox Jobs Directory. But later that same day the Chief of Staff leaned across the desk and shook my hand.

“Congratulations,” he said.

“You’ve got the job.”

It was the proudest day of my life.

It had been a very long journey to get inside the editorial floor of The Sydney Morning Herald.

In the literally thousands of stories that would follow, an equally long journey lay ahead.

Now, against a backdrop of outrageous government assaults on freedom of speech in my country, it is as if I can hear the voices of state operatives who follow my every key stroke.

Sometimes, with so many newly arrived migrants from authoritarian countries working in the public service, I swear I can hear them explaining to each other that in a democracy writers and journalists really do have the right to criticise the authorities.

That you can’t arrest people because they refuse to believe in the government narrative.

It has been a very long journey indeed.

Adapted from the upcoming memoir Hunting the Famous.

John Stapleton worked as a journalist on The Sydney Morning Herald and The Australian for more than 20 years.