New life in a distant land: [1 All-round Country Edition]

Stapleton, John. The Australian; Canberra, A.C.T. [Canberra, A.C.T]08 Nov 2005: 11.

Stapleton, John. The Australian; Canberra, A.C.T. [Canberra, A.C.T]08 Nov 2005: 11.

Abstract

The Dreadnought Scheme got its name after a group of patriotic Australians, concerned at German naval expansion in the build-up to World War I, decided to raise money to buy a battleship. When the government rebuffed their offer, they decided to defend Australia by importing British youths to work on rural properties with the then fashionable intention of boosting Australia’s white population.

British youth migration was later expanded to include the better- known Big Brother Movement, under which adult Australians acted as guardians for the migrant youths. There are now about 30 Dreadnought boys left in Australia. All are in their 90s. The survivors gathered in Sydney yesterday for a reunion and to launch Likely Lads and Lasses: Youth Migration to Australia 1911-1983, a book about their adventures and experiences, published by the Big Brother Movement.

Teenage girls by law had to go into domestic service, with church organisations, state governments and patriotic bodies all working to bring them out. In 1928, for example, Australia recruited more than 3000 domestics. They were released from their obligations by 21 or earlier if they married, as many did. They often went on to rear large families. Although most of them were filled with hope and excitement as they disembarked from the boats, some soon found themselves homesick and isolated on remote farms. But their efforts and those of their many descendants profoundly influenced Australia’s development.

Full Text

Thousands of British teenagers responded to an Australian immigration drive in the early 20th century, writes John Stapleton

NOEL Fidler will never forget the day he landed in Australia from England almost 80 years ago. Fidler had been lured to the Great South Land by an ambitious campaign that promised 50,000 unaccompanied British youths a new life in a faraway country.

“I was 17, I was doing my Cambridge University entrance exams,” Fidler recalls. “It was already the Depression in England and universities weren’t taking any new students. Instead of going to university I came to Australia. When we went ashore there was a drunk standing on the dock. The first words I heard were his: `Bloody Pommy bastards.”‘

Fidler, who turns 97 on Christmas Day, worked on farms for a couple of years before going into business. His biggest regret is that he never went to university, but he proudly points out there are now eight university degrees in his family, five of them earned by his grandsons.

“I have had a good life,” he declares. “We were young boys from England, Ireland and Scotland. We were all on our own, we had to make friends among ourselves. Until we got girlfriends. We’re getting pretty scarce now.”

Fidler is one of the surviving Dreadnought boys: a group of 7456 unaccompanied British youths who were brought to Australia in the early 20th century to work the land, populate the nation and defend its borders.

The first batch of 12 left London back in 1911. When they arrived in Sydney seven weeks later, they were described in the press as “fine, strapping young English fellows”. They were the beginning of a wave of 50,000 unaccompanied British teens, mostly aged about 15 or 16, who migrated to Australia during the next few decades under a range of different programs.

The Dreadnought Scheme got its name after a group of patriotic Australians, concerned at German naval expansion in the build-up to World War I, decided to raise money to buy a battleship. When the government rebuffed their offer, they decided to defend Australia by importing British youths to work on rural properties with the then fashionable intention of boosting Australia’s white population.

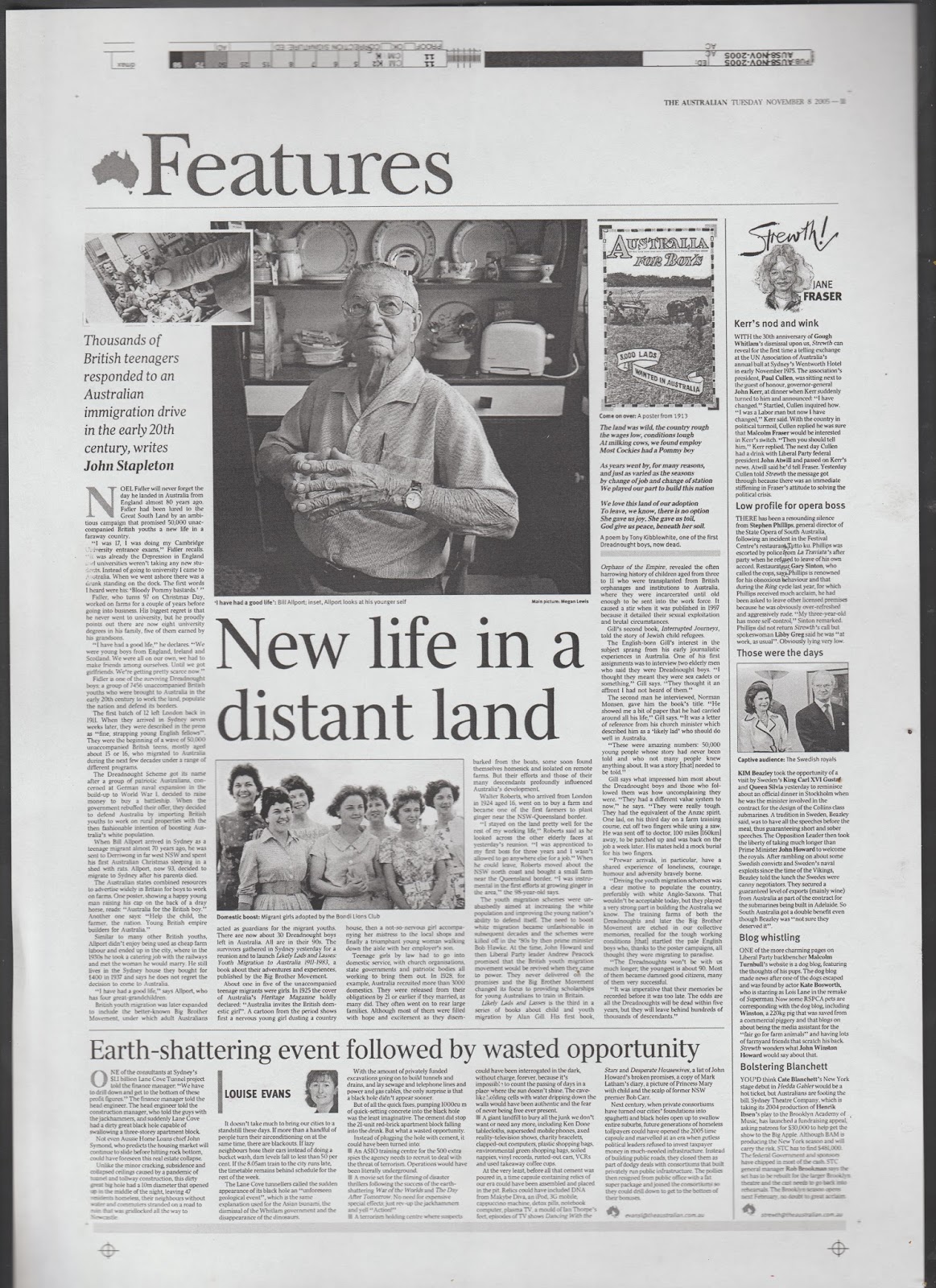

When Bill Allport arrived in Sydney as a teenage migrant almost 70 years ago, he was sent to Derriwong in far west NSW and spent his first Australian Christmas sleeping in a shed with rats. Allport, now 93, decided to migrate to Sydney after his parents died.

The Australian states combined resources to advertise widely in Britain for boys to work on farms. One poster, showing a happy young man raising his cap on the back of a dray horse, reads: “Australia for the British boy.” Another one says: “Help the child, the farmer, the nation. Young British empire builders for Australia.”

Similar to many other British youths, Allport didn’t enjoy being used as cheap farm labour and ended up in the city, where in the 1930s he took a catering job with the railways and met the woman he would marry. He still lives in the Sydney house they bought for pound stg. 400 in 1937 and says he does not regret the decision to come to Australia.

“I have had a good life,” says Allport, who has four great- grandchildren.

British youth migration was later expanded to include the better- known Big Brother Movement, under which adult Australians acted as guardians for the migrant youths. There are now about 30 Dreadnought boys left in Australia. All are in their 90s. The survivors gathered in Sydney yesterday for a reunion and to launch Likely Lads and Lasses: Youth Migration to Australia 1911-1983, a book about their adventures and experiences, published by the Big Brother Movement.

About one in five of the unaccompanied teenage migrants were girls. In 1925 the cover of Australia’s Heritage Magazine boldly declared: “Australia invites the British domestic girl”. A cartoon from the period shows first a nervous young girl dusting a country house, then a not-so-nervous girl accompanying her mistress to the local shops and finally a triumphant young woman walking down the aisle with her employer’s son.

Teenage girls by law had to go into domestic service, with church organisations, state governments and patriotic bodies all working to bring them out. In 1928, for example, Australia recruited more than 3000 domestics. They were released from their obligations by 21 or earlier if they married, as many did. They often went on to rear large families. Although most of them were filled with hope and excitement as they disembarked from the boats, some soon found themselves homesick and isolated on remote farms. But their efforts and those of their many descendants profoundly influenced Australia’s development.

Walter Roberts, who arrived from London in 1924 aged 16, went on to buy a farm and became one of the first farmers to plant ginger near the NSW-Queensland border.

“I stayed on the land pretty well for the rest of my working life,” Roberts said as he looked across the other elderly faces at yesterday’s reunion. “I was apprenticed to my first boss for three years and I wasn’t allowed to go anywhere else for a job.” When he could leave, Roberts moved about the NSW north coast and bought a small farm near the Queensland border. “I was instrumental in the first efforts at growing ginger in the area,” the 98-year-old says.

The youth migration schemes were unabashedly aimed at increasing the white population and improving the young nation’s ability to defend itself. The need to boost white migration became unfashionable in subsequent decades and the schemes were killed off in the ’80s by then prime minister Bob Hawke. At the time, John Howard and then Liberal Party leader Andrew Peacock promised that the British youth migration movement would be revived when they came to power. They never delivered on the promises and the Big Brother Movement changed its focus to providing scholarships for young Australians to train in Britain.

Likely Lads and Lasses is the third in a series of books about child and youth migration by Alan Gill. His first book, Orphans of the Empire, revealed the often harrowing history of children aged from three to 11 who were transplanted from British orphanages and institutions to Australia, where they were incarcerated until old enough to be sent into the work force. It caused a stir when it was published in 1997 because it detailed their sexual exploitation and brutal circumstances.

Gill’s second book, Interrupted Journeys, told the story of Jewish child refugees.

The English-born Gill’s interest in the subject sprang from his early journalistic experiences in Australia. One of his first assignments was to interview two elderly men who said they were Dreadnought boys. “I thought they meant they were sea cadets or something,” Gill says. “They thought it an affront I had not heard of them.”

The second man he interviewed, Norman Monsen, gave him the book’s title. “He showed me a bit of paper that he had carried around all his life,” Gill says. “It was a letter of reference from his church minister which described him as a `likely lad’ who should do well in Australia.

“These were amazing numbers: 50,000 young people whose story had never been told and who not many people knew anything about. It was a story [that] needed to be told.”

Gill says what impressed him most about the Dreadnought boys and those who followed them was how uncomplaining they were. “They had a different value system to now,” he says. “They were really tough. They had the equivalent of the Anzac spirit. One lad, on his third day on a farm training course, cut off two fingers while using a saw. He was sent off to doctor, 100 miles [160km] away, to be patched up and was back on the job a week later. His mates held a mock burial for his two fingers.

“Prewar arrivals, in particular, have a shared experience of loneliness, courage, humour and adversity bravely borne.

“Driving the youth migration schemes was a clear motive to populate the country, preferably with white Anglo-Saxons. That wouldn’t be acceptable today, but they played a very strong part in building the Australia we know. The training farms of both the Dreadnoughts and later the Big Brother Movement are etched in our collective memories, recalled for the tough working conditions [that] startled the pale English boys who, thanks to the poster campaigns, all thought they were migrating to paradise.

“The Dreadnoughts won’t be with us much longer; the youngest is about 90. Most of them became damned good citizens, many of them very successful.

“It was imperative that their memories be recorded before it was too late. The odds are all the Dreadnoughts will be dead within five years, but they will leave behind hundreds of thousands of descendants.”

The land was wild, the country rough

the wages low, conditions tough

At milking cows, we found employ

Most Cockies had a Pommy boy

As years went by, for many reasons,

and just as varied as the seasons

by change of job and change of station

We played our part to build this nation

We love this land of our adoption

To leave, we know, there is no option

She gave us joy, She gave us toil,

God give us peace, beneath her soil.

A poem by Tony Kibblewhite, one of the first Dreadnought boys, now dead.

Word count: 1579