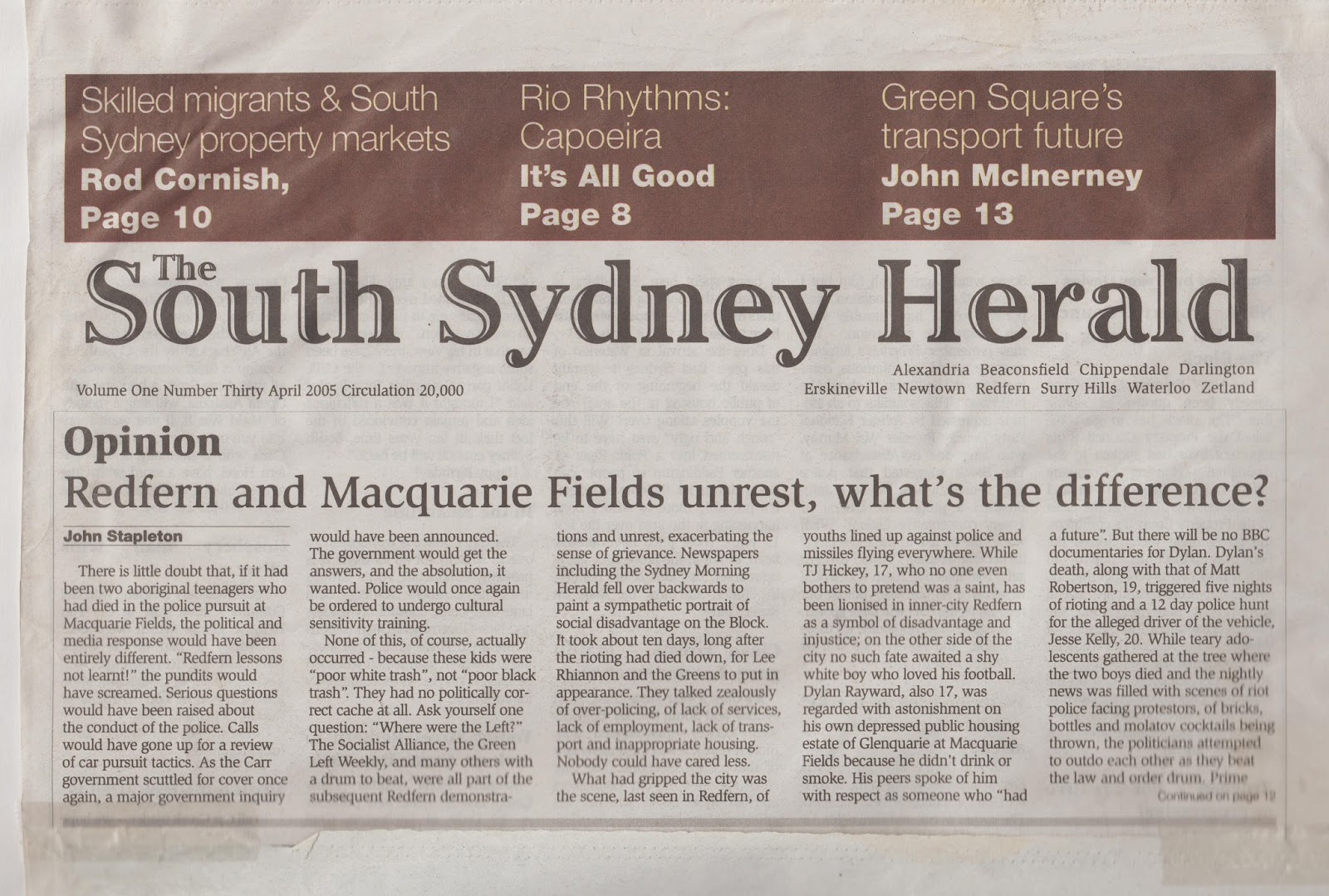

Published South Sydney Herald 2005

OPINION

John Stapleton

THERE is little doubt that if it had been two aboriginal teenagers who

had died in the police pursuit at Macquarie Fields the political and

media response would have been entirely different.

Redfern lessons not learnt, the pundits would have screamed. Serious

questions would have been raised about the conduct of the police.

Calls would have gone up for a review of car pursuit tactics. As the

Carr government scuttled for cover once again, a major government

inquiry would have been announced. The government would get the

answers, and the absolution, it wanted. Police would once again be

ordered to undergo cultural sensitivity training.

None of this, of course, actually occurred – because these kids were

“poor white trash”, not “poor black trash”. They had no

politically correct cache at all.

Ask yourself one question: where were the Left?

The Socialist Alliance, the Green Left Weekly, and many others with a

drum to beat were all part of the subsequent Redfern demonstrations

and unrest, exacerbating the sense of grievance. Newspapers including

the Sydney Morning Herald fell over backwards to paint a sympathetic

portrait of social disadvantage on the Block.

It took about ten days, long after the rioting had died down, for Lee

Rhiannon and the Greens to put in appearance. They talked zealously of

over-policing, of lack of services, lack of employment, lack of

transport and inappropriate houising. Nobody could have cared less.

What had gripped the city was the scene, last seen in Redfern, of

youths lined up against police and missiles flying everywhere.

While TJ Hickey, 17, who no one even bothers to pretend was a saint,

has been lioinised in inner-city Redfern as a symbol of disadvantage

and injustice; on the other side of the city no such fate awaited a

shy white boy who loved his football. Dylan Rayward, also 17, was

regarded with astonishment on his own depressed public housing estate

of Glenquarie at Macquarie Fields because he didn’t drink or smoke.

His peers spoken of him respect as someone who “had a future”. But

there will be no BBC documentaries for Dylan.

Dylan’s death, along with that of Matt Robertson, 19, triggered five

nights of rioting and a 12 day police hunt for the alleged driver of

the vehicle, Jesse Kelly, 20.

While teary adolescents gathered at the tree where the two boys died

and the nightly news was filled with scenes of riot police facing

protestors, of bricks, bottles and molatov cocktails being thrown, the

politicians

attempted to outdo each other as they beat the law and order drum.

Prime Minister John Howard backed the police “150 per cent”,

outdoing the NSW Premier Bob Carr, who only backed them 100 per cent.

Opposition leader John Brogden repeatedly critised the police and the

state government for their softly softly approach. As far as he was

concerned a full-scale crackdown on the first night would have solved

the problem.

None of them expressed anything but passing sympathy for the two dead young

men, Dylan and Matt, their family, or their

friends.

Yet these kids lives on a public housing estate had been taxpayer

funded, as had their deaths during a police chase. Their entire lives

had been dictated by the policies of the politicians now so ready to

condemn them.

I covered as a reporter both the Redfern riots and the problems at

Macquarie Fields. There were very clear similarities and very clear

differences between the two.

The riots at Redfern following the death of Thomas “TJ” lasted one

night and were fuelled by alcohol as much as by grief.

At Macquarie Fields the riots stretched over a week and

were fuelled by far more than just alcohol.

Unlike the politicians or the ruthless sentiment on talkback radio, a

number of reporters felt instinctively that this was a “faultline”

type story, that this was the beginning of what was likely to be more

such incidents; that the Lucky Country really was only lucky for some,

that the so-called booming economy had barely touched many. In some

ways this was like the first story falling off the end of a conveyer

belt. There are bored, keyed up, restless, unemployed youth everywhere

on the public housing estates of Ayrds, Minto, Claymore, Glenquarie

and across the city, including Redfern, these children who were to

inherit the earth after decades of progressive policies.

One of the reasons the talk-back coverage was so vicious on the

Macquarie Fields riots is that for many of the working poor the

new prosperity of Australia doesn’t mean much but the chance to sit in

traffic and work all day in an eternally frustrating grind; to pay

multiple taxes for a vast government bureaucracy and political and

judicial system which improves their

lives barely a jot if at all.

The conduct of the denizens of Macquarie Fields went from a grief

stricken group wanting to tell their story and vent their outrage to

hostile, foul-mouthed and abusive. This was not a group which was

sophisticated enough to use the media or sense when they might be

sympathetic.

Many reporters were emotionally moved by the cards, flowers and totems

that were placed at the scene of the two boys deaths – the cigarettes

taped to to the tree, the undrunk can of Woodstock Bourbon and Coke,

the many messages of grief, “RIP Boys, see ya on the other side”.

One newspaper reporter who covered the riots said: “There were little

17 year olds crying at the tree where the

boys died. The whole community was really emotional. The vast majority

believed the police pushed the situation too far. It was obvioius that

tensions have been simmering for quite some time. The car crash was

simply the precipitating event. The boys just feel totally powerless.

They have no voice. Everyone calls them criminals, that may be true,

but they were very kind, very

charming to me. They let me into their lives. Just because they stole

cars didn’t mean they were bad people. A lot of them were very young

and very proud parents. They had a lot of good qualities, and a lot of

genuine care for their kids and how they were going to bring them

up.”

Phil Black, a reporter at Channel Seven, said the public simply don’t

understand what

the feeling is in these neighbourhoods, and

particularly what drives it, why they are so angry and disaffected as

they are. “I don’t think the guys do themselves any favours It

is easy to sympathise. but when we become the targets, bottles and

abuse, it is difficult for that sympathy to take too much of a hold. I

think it is generational. A lot has been said about poor

neighbourhoods like this being concentrated areas of underprivilege,

and all the social problems sprout from this, but these are

multi-generational hotspots for people who are angry and disaffected.

Over generations people are becoming alienated. These are areas where

Educatiom,. resources and opportunities are lacking.

“Over time, an us and them mentality develops. These communities develop close

connections between each other. there is a strong sense of community.

they tend to look at others as outsiders. They are sheeting blame

towards the police and the media for their situation. The classic

example, is they would throw bottles, rocks and abuse, and then turn

around and say: `I hope you guys are going to make us look good’. They

accuse us of not having told their story, of not capturing how they

feel and why and misrepresenting the facts, but ultimately, the

pictures of them throwing bottles, it’s hard to misrepresent that.

“It is obviously a very complex problem. Politicians are kidding

htemselves if they don’t think social propblems are not behind this

level of anger and disaffecting. They say it is possible to rise above

your circumstances, but as theose circumstances become tougher over

generations, it becomes even harder still to rise above those circumstances.”

If any of the reporters bothered to turn on talk-back radio they

copped a chilling contrast between what they had witnessed on the

streets and what was filling the airwaves. John Law’s at 2UE called

them “louts” and suggested to one caller who claimed to be friends of

the pair who had died that she was either “stupid or as bad as they

are” and suggested she should get new friends. He dismissed the

graffiti littering the suburb – “Cops Kill Kids” – painted on streets,

pavements and walls, as “incredible”.

Over at 2GB, Ray Hadley ran hot on the Macquarie Fields riots from the

beginning. He said the majority of residents were law abiding and Ken

Maroney and Carl Scully needed to remove unwanted criminals from that

environment. Hadley said that at the end of the day people needed to

take responsibility instead of the rubbish, “I live at Macquarie

Fields, I have no hope”, it should not be an impediment. One woman,

representative of many, said they should get off their bums and do

something with themselves.

Australia’s number one talkback host Alan Jones spoke of the

ineptitude of decision makers which had left front line police

enduring a “disgusting state of affairs” as they were pelted with

rocks, bricks and bombs night after night. “We can do without the

Kleenex tissues and the bleeding hearts,” he said, labelling people

such as the fugitive driver Kelly as “criminals”. He urged the police

to “toughen up and clean up”.

Senior political reporter with the Sydney Morning Herald Paola Totaro

said she had felt throughout the week that the response was

simplistic. “My view from the

beginning, there was Carr, and Moroney, and they are speaking from a

completely different generation, a generation that may have grown up in

disadvantage, but they weren’t subjected to the same pressures that

this generation has; of parents who are alcohol and drug affected;

often unemployed and second generation unemployed. The personal

responsibility answers of the politicians and the various leaders was

not only simplistic but idiotic, to be honest. They are white men who

have reached the peak of their careers, who

were teenagers 40 or more years ago.

“The world has changed. We had to inject some intelligence and

analysis, and more importantly compassion, in to our coverage of what has

happened and why.

“The talk back commentators are white middle class men, again at the

peak of their careers and the peak of their earning powers. They have

completely lost sight of the lives of many of the battlers they

purport to represent.”

The deaths of very few of us will provoke such civil unrest, or be

greeted with such genuine grief, as did the deaths of these two young

men in a stolen car very late one Friiday night on one of the city’s

most depressed housing estates; Dylan Rayward, 17 and Matt Robertson,

19.

Dylan’s body was carried through an honour guard of young

football players from the Ashton Junior Rugby League team from

Liverpool where he trained. His No 13 Jersey was laid on the coffin.

As sobs from more than 200 friends, family and locals were heard

throughout the chapel, three of Dylan’s football coaches gave moving

testimony to the boy’s talents as a player and qualities as a person.

The family, some of whom had been let out of jail especially to attend

the funeral, sat at the front of the chapel, holding on to each other

as

they frequently burst into tears.

These were the “criminals” so roundly condemned.