Big Tech’s hefty manipulation of the Covid narrative is driving many dissenting Australians away from Facebook, Google and WhatsApp to less compromised applications less manipulated by governments and military contractors.

In the age of surveillance capitalism, both Facebook and Google have also suffered from a perceived lack of privacy for users.

And thus it is that the messaging app Telegram, begun by two Russian oligarchs who have refused to bow to pressure to provide backdoor access to governments and security organisations, is enjoying a surge in popularity.

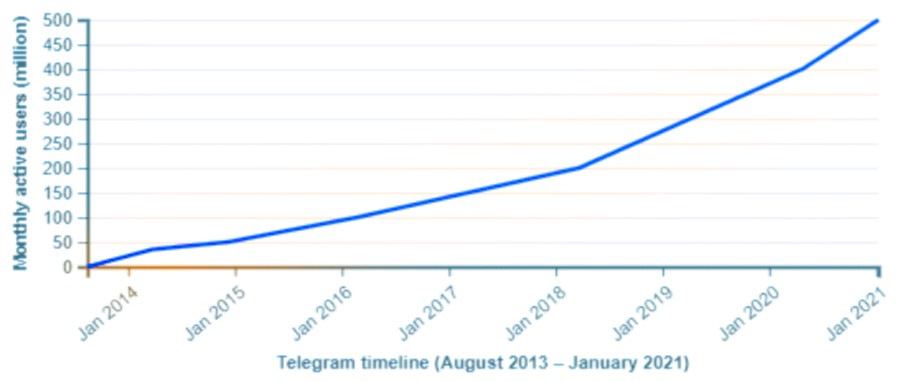

Founded in 2013, Telegram was the most downloaded app in the world for January this year. It recently topped one billion downloads and has 500 million active users each month.

Plenty of them these days are Australians.

Groups now using Telegram as a matter of course include AFL solicitors, which recently ran a major case against mandated vaccines through the NSW Supreme Court and is involved in the high profile case of Monica Smit from Reunite Democracy. Advocate Me, which has provided legal and promotional resources to groups like Cops for Covid Truth, has a well patronised channel, as do others such as National Educated United, which is leading the push by teachers objecting to vaccination mandates.

In October 2013, Telegram announced that it had 100,000 daily active users. On 24 March 2014, Telegram announced that it had reached 35 million monthly users and 15 million daily active users. In October 2014, South Korean governmental surveillance plans drove many of its citizens to switch to Telegram. In December 2014, Telegram announced that it had 50 million active users, generating 1 billion daily messages, and that it had 1 million new users signing up on its service every week. Traffic doubled in five months with 2 billion daily messages.

In February 2016, Telegram announced that it had 100 million monthly active users, with 350,000 new users signing up every day, delivering 15 billion messages daily.

On 14 March 2019, Pavel Durov claimed that “three million new users signed up for Telegram within the last 24 hours.” Durov did not specify what prompted this flood of new sign-ups, but the period matched a prolonged technical outage experienced by Facebook and its family of apps, including Instagram.

On 8 January 2021, Durov announced in a blog post that Telegram had reached “about 500 million” monthly active users.[50]

On 5 October 2021, Telegram gained over 70 million new users as a result of an outage on Facebook and its affiliates.

For once the advertising logo is correct. The headline grabbing mobile app Telegram promotes itself as a “new era of messaging”. It uses military grade encryption to ensure the privacy of communications. That only a few short years ago it was one of the most popular encryption programmes for jihadists and Islamic State supporters is for some beside the point. You might as well criticise the mujahedeen for driving cars.

For others it is entirely the point.

A new era of encryption products has created a nightmare for security agencies. It is not just the FBI in the US arguing with Apple over whether or not it can access encrypted data from mobile phones to disentangle terror plots. Security agencies worldwide are being stumped by technology which ensures the privacy of communications and anonymity of users.

In 2015 Islamic State claimed responsibility for the Paris massacre where 130 people were killed, the shooting down of a Russian airline and other attacks, all on Telegram.

Ultimately Telegram was forced to purge ISIS content from its system.

Since those early days Australian authorities have gone into hyperdrive over their surveillance of the Australian population. As the saying goes, the surveillance of the average citizen is now well beyond that feared by the clinically paranoid.

At the same time as as metadata laws have escalated government surveillance of civilians to a level beyond anything even George Orwell ever imagined, a new generation of tech-savvy jihadists leapt onto encryption apps to share their triumphs and despairs, plots, propaganda and inspiration.

A terror plot can be hatched without leaving a whisper in cyberspace. Messages can be set up to self destruct within a second, while end-to-end encryption combined with the use of a Virtual Private Network which scatters IP addresses around the globe ensures that the user cannot be traced and the communications cannot be decoded.

So confident is Telegram that its messaging cannot be decrypted, in 2014 it began offering a $US300,000 reward for anyone who could do so.

The company was founded by Russian brothers Nikolai and Pavel Durov, who based themselves in Berlin after falling out with Vladimir Putin.

When asked if he was losing sleep knowing terrorists were using his platform, Pavel Durov is reported to have said: “The right for privacy is more important than our fear of bad things happening, like terrorism.”

The Telegram app was made even more appealing by the introduction of “channels”, which means anyone can broadcast anything they like to their chosen audience without revealing the identity or location of themselves or their followers.

Back in the day, despite all the Australian government talk of making it more difficult to access Islamic State’s online propaganda, it took only seconds to find the Islamic State Telegram channel English Nashir, under a banner displaying the Islamic State flag and logo and with the words: Come Forth to Your State!

If you do not have a Telegram account already interested parties were prompted to join.

There were also numerous links to online propaganda, from IS linked Twitter accounts to the latest copy of their expensively produced high quality magazine Dabiq.

Once connected through Telegram, what people are watching, reading or listening to or who they are communicating with immediately becomes immune from eyes of the authorities.

Technology expert and CEO of consulting firm Eye on the Future Morris Miselowski said there was no solution to the problem posed for security companies.

“There is a dichotomy,” he said. “Consumers are screaming out for programs which can’t be hacked into, but we get disappointed when they can’t be hacked into. We want the technology. we just don’t want the bad guys to use it. We go around in circles.

“Humans will communicate, and we are increasingly doing it in digital spaces. We can’t yell at Telegram and Facebook, we might as well be yelling at humans for using it.

“Telegram is in the middle of the road which has been quite long and will be much longer.”

Critics call apps such as Telegram the command and control centres of terrorists, while British Prime Minister David Cameron attempted to push legislation through parliament blocking companies including Apple and Google from using encryption technology so sophisticated not even they can decode it.

But many others warn that yet more privacy threatening legislation is not the way to go.

Laurie Patton, head of the peak body Internet Australia, said that while they supported efforts to counter criminal activities, especially terrorism, knee-jerk reactions such as the Data Retention Act pushed through parliament by Tony Abbott were doomed to failure. “We believe that informed public debate should proceed any legislative changes that could adversely affect the essential open and trustworthy basis on which the Internet has been developed,” he said.

Ross Schulman, Senior Counsel for the Open Technology Institute in the US, told The New Daily that when it came to encryption the the genie was already out of the bottle. there is not much that can be done to stop the use of encryption, precisely because so much of these products are either open source, or produced by companies not within the jurisdiction of our various governments. Legal mandates are bad policy for privacy, commercial, and cyber security reasons, and are often times simply unenforceable.

“The rise in these types of apps can be put down to two forces: First is advances in technology and usability that make these sorts of tools more and more available and easier and easier to use. Second is a growing awareness among the public that our lives today are digital and lived largely online and on our phones. They are our digital homes, and people are seeking to protect these devices in the same way we all seek to protect our physical homes.”

This piece was originally written in 2015 for The New Daily by editor of A Sense of Place Magazine John Stapleton and has been updated.