By John Stapleton

This week ten people were arrested in Melbourne for attending a protest against self-isolating, social distancing and tracking apps, the only real political protest in the country since climate demonstrations earlier in the year.

The government perpetrated scare on terror, however real or otherwise its basis, has morphed into Covid-19.

Whether it is currently fashionable or not, deemed unpatriotic or not, is correct or not, it is an entirely legitimate political view to argue that more harm will be done by the government’s actions, including shutting down the economy, than would have ever been done by the virus. That like so many other aspects of Australian life, we would have all been better off if the government had done nothing.

All normal democratic processes, including the right of assembly and the right to protest, have now been suspended across Australia.

This article was originally written in 2018.

It’s worth looking back at how we got here.

The democratic contract is broken.

The freedom of Australians to go about their daily lives without being watched by their government has vanished with barely a whisper of protest.

The war on terror has recast the relationship between liberty and security.

Oddly for such a geographically isolated nation, Australia has passed a larger and more oppressive body of anti-terror legislation than any other Western country.

One of Australia’s most oft cited experts in the field, Professor of Law at the University of New South Wales George Williams, argues that the rushed nature of more than 60 pieces of anti-terror legislation passed since 9/11 has shown up deep flaws in the Australian political system, including the lack of legal rights to privacy or freedom of speech.

“This government has seen some very significant expansions in the power of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), particularly the power to conduct Special Intelligence Operations.

“These powers can place it outside normal legal processes, and lie well outside the powers of similar agencies in the US and the UK.

“Journalists face up to a decade in jail for reporting on an SIO, even if it is in the public interest.

“There are inadequate checks and balances. In key areas the powers gifted to ASIO are disproportionate. There are a long list of things where the operation of ASIO now lies outside normal democratic values.”

Adviser to Wikileaks

Barrister Greg Barns, adviser to Wikileaks, argues that with the gifting of ever more powers to national security agencies, Australian democracy is dying.

He describes last year’s spectacle of Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and the state premiers lining up to declare their support for the arresting of suspects as young as 10 and their detention for 14 days without charge as sickening.

ASIO can act with virtual immunity and could, during the course of this detention, deprive people of sleep and refuse access to family members, a clear breach of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Mr Barns says: “ASIO has the capacity to invade every person’s every communication and movement. The use of taxpayer funds to surveil, harass and spy on NGOs and ethnic groups is now ASIO’s bread and butter.”

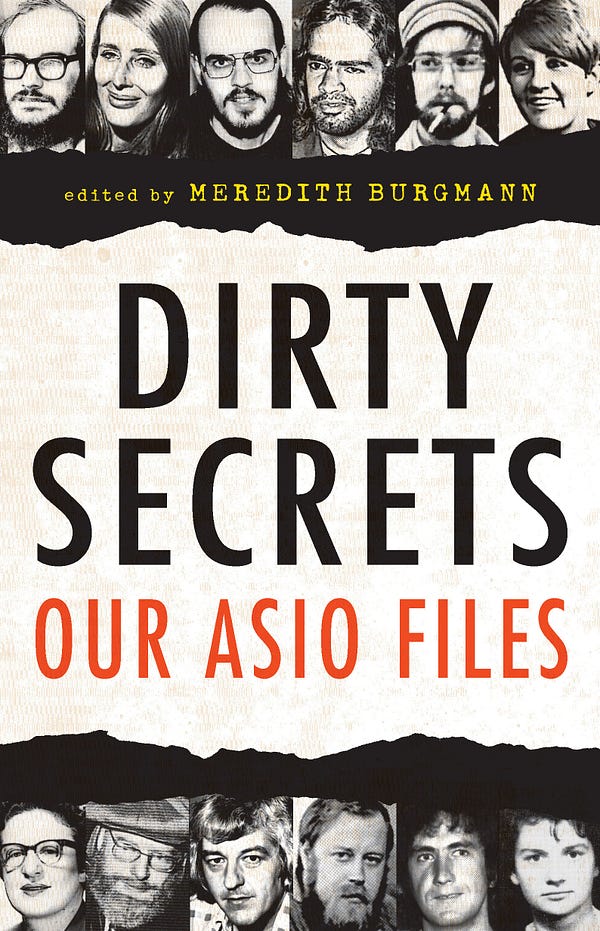

Dirty Secrets

The best pointer to the present is the past. Dr Meredith Burgmann’s book Dirty Secrets: Our ASIO Files revealed a long history of excessive surveillance of Australian citizens, and misuse of the information thus obtained.

Under the 30-year secrecy rules ASIO more than 10,000 files, often heavily redacted, have come to light. The organisation formed to root out subversion took upon itself to monitor everyone from gay activists to early feminists. The anti-intellectuality of a military ethos is evident throughout the files.

The targets invariably speak of the waste of public resources that went into their surveillance, and the often slipshod or inaccurate nature of the results.

Perpetrators Act Like Predators

Humans are mammals. If they feel they are being watched, they instinctively fear they are about to be eaten.

Surveillance causes the perpetrators to act like predators and the targets like prey.

Harvard’s Bruce Schneier, author of Data and Goliath, says psychologists, sociologists, philosophers, novelists and technologists have all written about the effects of surveillance. It creates ill health and strips people of their dignity.

“There’s a reason why surveillance states aren’t the ones that flourish; it’s profoundly inhumane,” he says.

The Australian government has ignored the negative consequences, hoping only for a docile population.

A Profound Victory

Journalist Glenn Greenwald, author of the book on Edward Snowden No Place to Hide, writes that this model of surveillance creates the illusion of freedom:

The compulsion to obedience exists in the individual’s mind. Individuals choose on their own to comply, out of fear that they are being watched. With the control internalised, the overt evidence of repression disappears because it is no longer necessary. It is a profound victory.

Of all the target groups, Muslims have been the most impacted by the expansion of the surveillance state. It contributes directly to estrangement and resentment, and to the extremism it is meant to resolve.

To a man, or woman, the Muslim minority regard Australia’s participation in Middle Eastern wars as akin to terror, placing them at direct odds with the government.

Muslim spokesman Keysar Trad says: “The fear relating to surveillance is eroding the level of trust of not only authority figures, but of ordinary people, who is monitoring, who is reporting, who is misreading what they see and hear.”

Reclaim Australia

On the opposite side of the panel, members of Reclaim Australia shrug off their surveillance, saying it’s a stupid waste of public money and they are not doing anything wrong.

Members of the group have already been interviewed by the intelligence services. They were obliged to sign contracts keeping the discussions secret.

Co-founder Catherine Brennan says:

“We are not radicals. Our views are not that far from a lot of Australians. We speak with counter-terrorist officers regularly. People will tell us things before they tell the police, they feel more comfortable with us.”

The Public Square Criminalised

The key to the lack of protest over ever increasing levels of surveillance lies with the nature of public debate.

There have long been rumours that agencies have placed personnel or informants throughout Australia’s media organisations.

For decades the CIA has spent millions manipulating the media, including placing personnel into key positions.

Thanks to the close relationship between American and Australian national security agencies, there is every reason to assume something similar is occurring in the Land Down Under.

Senior Journalist Andrew Fowler, author of one of the preeminent texts on Julian Assange, The Most Dangerous Man in the World: How One Hacker Destroyed Corporate and Government Secrecy Forever, has a new book out, Shooting the Messenger: Criminalising Journalism.

Hesays surveillance and anti-terrorism laws are introduced for several reason, one is to be “seen to be doing something”, in response to a perceived threat, often over-inflated by elements of the media. The laws have the added bonus of making the work of journalists far more difficult, particularly in the area of so-called national security.

As we learned from the Iraq War governments will fabricate the information to fit their argument for war. What they will resist at all costs is the publication or broadcast of anything which reveals their acts of deception and falsehood.

“The increased power given to executive government by surveillance and anti-terrorism laws is extremely dangerous,” Fowler says. “In a country where politics is increasingly dominated by appeals to nationalism and threats from outside, terrorism is a useful tool to keep a sometimes malleable population, fearful and controlled.

“The fear of terrorism is used by governments as a way of persuading populations to hand over billions of dollars to fund mass surveillance systems.

“Counter-terrorism, drug running and trapping child molesters are of marginal importance, but they are always the first put forward by executive government when they seek more power and more money to fund these ventures.

“These systems suck up vast amounts of material around the globe and use it mainly to further their economic, strategic and diplomatic objectives.”

Fowler says the question about why journalists often champion the increasingly intrusive level of state surveillance is intriguing.

“As the media has been weakened by lack of funding it has found it easier to follow the government line than to ask questions.

“Stories can be ‘covered’ without too much effort.

“Investigating the truth of what governments say about the necessity of increased surveillance and terrorism powers takes time, which many journalists simply don’t have.

“Some journalists do not have ‘historical memory’ of events like the Iraq War, and are unquestioning. Others, such as those in parts of the Murdoch media, support militaristic answers to democratic problems. And others are simply too scared to question power.”

Tuned Out

Tuned out, alienated by and now indifferent to the antics of the political class, the remarkable thing is how quickly the Australian public has accepted all of this: the data retention laws, the jailing of whistle-blowers and journalists, the extensive monitoring of social media by public servants.

Even the detention of ten year old children.

The devolution of the public broadcaster the Australian Broadcasting Corporation into little more than a government propaganda wing could not have been better illustrated than last year’s story of the Prime Minister’s pledge to introduce legislation to detain without charge people accused of terror related offenses without charge.

For their expert the ABC chose one of their own journalists, Barrie Cassidy, the flyblown presenter of Insiders each Sunday. He fulsomely, and shamefully, agreed with the government that a loss of civil liberties was necessary in the age of terror.

It was not as if critics were hard to find.

President of the Law Council of Australia, Fiona McLeod SC, said: “It’s the combined shock of having a pre-charge detention of up to 14 days and the revelation they’re going to seek to have this extended to the age of 10. We’re talking about grade four kids. This has crossed the line.”

The Most Dangerous Man Alive

One of Australia’s most famous sons, whistle-blower Julian Assange, has been ignored or reviled by his own government. Exactly the reason why the last word belongs to him:

“The world is not sliding, but galloping into a new transnational dystopia. This development has not been properly recognized outside of national security circles. It has been hidden by secrecy, complexity and scale. The internet, our greatest tool of emancipation, has been transformed into the most dangerous facilitator of totalitarianism we have ever seen. The internet is a threat to human civilization.

“These transformations have come about silently, because those who know what is going on work in the global surveillance industry and have no incentives to speak out. Left to its own trajectory, within a few years, global civilization will be a postmodern surveillance dystopia, from which escape for all but the most skilled individuals will be impossible. In fact, we may already be there.”

John Stapleton worked for more than 20 years as a staff reporter on The Australian and The Sydney Morning Herald.

A collection of his journalism is being constructed here.