Every inch of The Triumph of Death features chaos on a massive scale. It is as though the artist’s brush cannot keep up with the fanatical energy of death’s hordes, busy killing and harrowing wherever you look.

In the foreground, a skeleton is cutting a man’s throat while not far away a starving dog eats a woman’s face. On a hillside further back on the right, a dead man has been skinned and hung from a tree. His head is thrown backward and held in the branches by a metal pin that passes through his skull.

Richard B Woodward. WSJ.

Dulle Griet

1563, panel, 117.4 × 162 cm

Antwerp, Museum Mayer van den Bergh

© Museum Mayer van den Bergh

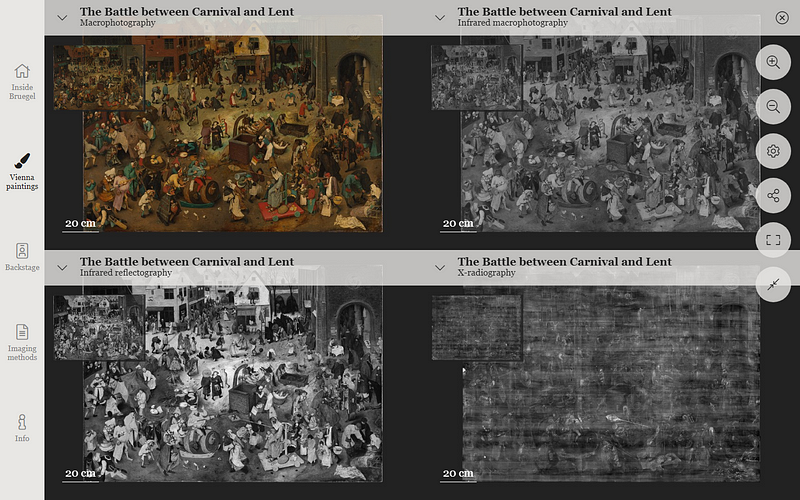

Inside The Battle between Carnival and Lent

The Battle between Carnival and Lent

1559, oak panel, 118 × 164,5 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery

© KHM-Museumsverband

The subversive — and, to this day, little-understood — qualities of Bruegel’s work often took the shape of panoramic landscapes dotted with bursts of everyday activity. Alternately interpreted as celebrations or critiques of peasant life, Bruegel’s paintings feature a pantheon of symbolic details that defy easy classification: A man playing a stringed instrument while wearing a pot on his head could, for example, represent a biting indictment of the Catholic Church — or he could simply be included in hopes of making the viewer laugh.

Meilan Solly. Science Journalist. The Smithsonian Magazine.

The Conversion of Saul

1567, oak, 108 x 156 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery

© KHM-Museumsverband

X-ray imaging of a 1559 work, “The Battle Between Carnival and Lent,” reveals macabre features masked in the final product, including a corpse being dragged in a cart and a second dead body lying on the ground. Infrared scans further highlight the small changes Bruegel made prior to completing the painting, with a cross adorning a baker’s peel transformed into a pair of fish. The cross blatantly refers to the church, while the fish — a traditional Lent delicacy — offers a subtler nod to Christ.

Meilan Solly. Science Journalist. The Smithsonian Magazine.

The Peasant Bruegel

The Adoration of the Magi in the Snow

1563, wood, 35 × 55 cm

Swiss Confederation, Federal Office for Culture, Collection

Oskar Reinhart ‘Am Römerholz’, Winterthur

© Collection Oskar Reinhart ʻAm Römerholzʼ, Winterthur

The Haymaking

1565, oak panel, 114 × 158 cm

Prague, The Lobkowicz Collections, Lobkowicz Palace, Prague Castle

© The Lobkowicz Collections

Anyone interested in art knows the name Bruegel.

The most important Netherlandish painter and draughtsman of the 16th century had already achieved great fame during his own lifetime, but was largely forgotten in the 18th and 19th centuries and only rediscovered by art historians in the early 20th century.

His variety of subjects, which draw on the earlier pictorial traditions of Hieronymus Bosch and the latter part of the Middle Ages, and their originality of execution, still elicit great fascination from viewers today.

For their generosity and great faith in entrusting us with such fragile works — all among the most precious holdings of their respective collections — we extend our wholehearted thanks to the numerous institutions and lenders from around the world who have contributed, and who have collegially and constructively supported this project.

The Return of the Herd

1565, oak, 117 × 159 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery

© KHM-Museumsverband

It will be the very first time ever that the full range of works by Pieter Bruegel the Elder will be on view. More than half of his surviving paintings, drawings and prints will be reunited, works that only leave the walls of the museums that house them on the rarest of occasions.

An exhibition such as this therefore ranks among the most extraordinary museum events, and it will most likely not occur again within this century.

The Suicide of Saul

1562, oak panel, 33.5 × 55 cm

Kunsthistorisches Museum Vienna, Picture Gallery

© KHM-Museumsverband

We repeatedly seek new paths of access into the work of this great master.

An acute observer, Bruegel often holds up a mirror to the viewer, something that makes his work highly immediate and sometimes unsettling, thus giving it a fascinating connection with the here and now.