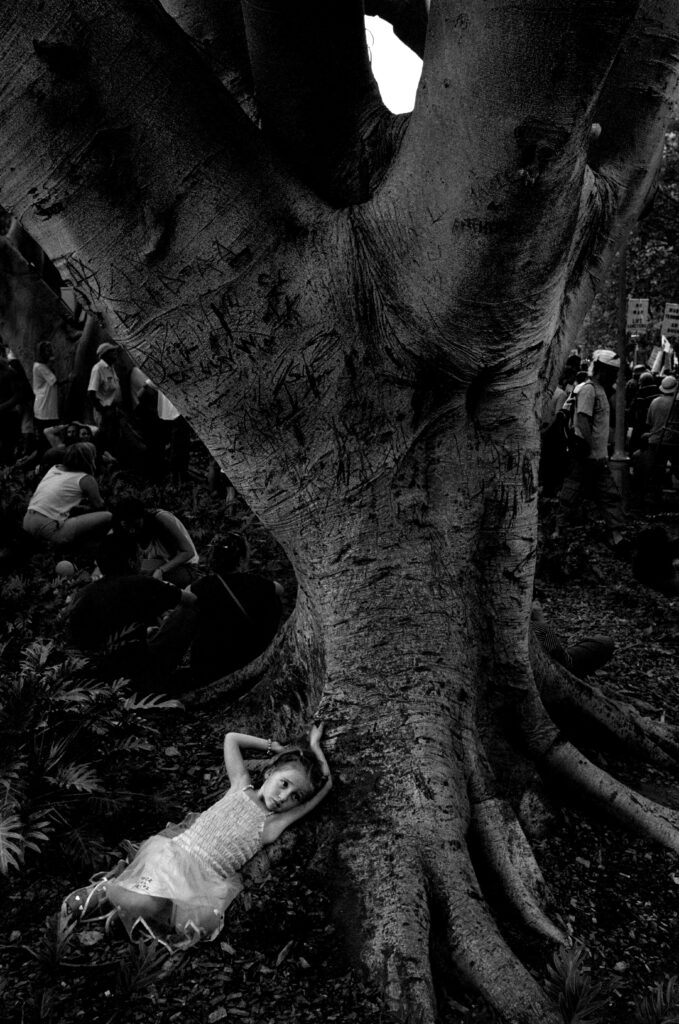

Photography by Dean Sewell

THE THINGS HE REMEMBERED MOST STARKLY from the early months of the Covid Era were empty trains churning through the night, a sense of threat as everything was altered, military helicopters hovering over a deserted Sydney Harbour, empty streets, silent suburbs, and dread, mostly dread.

Perhaps one of the single most extraordinary things about the way Covid-19 played out in Australia in early 2020 was that polls showed faith in both media and government went up.

Learned types in little read journals dismembered the government’s confusing and contradictory messaging. But few Australians read newspapers anymore, much less academic journals.

The wildly inaccurate nature of initial modeling might have proffered some excuse for the Australian government’s mishandling of the Covid crisis. However within weeks of it all beginning epidemiologists from some of the world’s leading institutions were speaking out, warning that lockdowns were an inappropriate policy response.

The geniuses in the Australian government ignored all the cautionary tales, all the world experts speaking out saying lockdowns did more harm than good, that they were a radical social experiment going against decades of epidemiological wisdom.

For all the damage they caused, for all the spiritual, individual and communal derangement involved, if lockdowns had a face, it was demonic.

As a retired journalist Old Alex, to adopt a pseudonym from previous books, was quick to make the game clear: a government cherry picking experts to suit their personal agendas and implement a dangerous new authoritarianism was deceit.

Not telling the Australian public there were multiple sides to this argument was deceit.

The beneficiaries of all this deceit, as soon became obvious, were incumbent governments; conservative at Federal level, Labor in most of the states. A frightened population clung to what they knew; trusted their elected representatives; accepted the abrogation of their freedoms.

There was a strange moment in that island nation, somewhere between support, submission, compliance and an unknown threat. It was what would come next, including a runaway train of government and administrative maladministration, that would destroy the country.

There were so many signs a signal derangement was about to pierce through everything; so many moments of precognition lighting up across the globe. Every pundit on the planet was active. Medical experts competed for attention.

Data released in April of 2020 by the Australian Bureau of Statistics in conjunction with the Australian Taxation Office showed that at least six percent of workers had lost their job over the previous month, with the accommodation, food, arts and recreation industries smashed by the impact of the government’s response to the coronavirus.

While the fall in jobs was similar for both women and men, there were large differences across age groups, with those under twenty and over seventy hardest hit.

More than 870,000 people lost their jobs in those first few months.

***

***

In the car parks of Oak Flats, a working class suburb two hours south of Sydney where Old Alex had unexpectedly found himself, as night settled there was a deep sense of threat in the air. Potential friends became potential enemies just like that. Customers were rushing into Woolworths as if it was their last chance to buy provisions before the End Times, barely looking at each other, they were so clearly frightened. What was once a gruff, no-nonsense working class suburb was already diminished.

Nearby Woollies, the once sacred, most beautiful of waterways Lake Illawarra now reminded him more of Pokhara in Nepal in the early 1970s. He was there as a wannabe habitué of the Coca Cola trail. With electricity a luxury, only a few lights from small hotels or grand houses punctured the Nepalese night, and the only sound was of generators grumbling through the tight mountain air; or the occasional shout from some local celebration. Mostly there was silence.

The same was now true of Lake Illawarra, which in 2020 was already intensely suburbanised. People were dug in inside their houses, afraid to go out in case they encountered the virus, which might as well have been Ebola for all the drama, fear and exaggeration which surrounded it.

Old Alex was out of sorts, with himself but most of all with the prevailing sentiment.

The country was rallying, much to his disbelief, around the Prime Minister, Scott Morrison. There were pieces in what remained of legacy media lauding “the father of the nation”. For crying out loud!

An old journalist who knew, if nothing else, how media narratives were manufactured and how badly the populace was being served, how heavily manipulated they were, Alex fumed daily about the paucity of genuine information, every politician in the country taking the opportunity to grandstand in front of television cameras. And, immorally to his mind, panicked the population.

***

Australia had not seen quality governance for many years, and the current crop of reckless politicians had as their natural constituents the Very Big End of Town. The closest any of the nation’s leaders got to mingling with the likes of those who lived in Oak Flats, “Oakflattigans” as they were sometimes known, was every few years at election time.

Every last one of those sycophantic stories lauding the nation’s leaders sickened Old Alex to the core. His generation of journalists would have been ashamed to give credit where credit was not due.

A former News Editor of his at The Sydney Morning Herald back in the 1980s, Richard Glover, now a well known radio personality on the taxpayer funded ABC and a star turn at the gatherings of the city’s burgeoning bourgeoisie, wrote a piece for The Washington Post titled “Australia’s leader is winning the argument on the coronavirus”.

“Australians like to see themselves as rebellious people, distrustful of authority – but the coronavirus has changed that.

“While small protests against the lockdowns have erupted in the United States, and some in Britain have insisted on their right to party, in Australia we’re mostly doing what we’re told.

“In Sydney, public transport use is down to levels not seen for nearly 100 years. Attendance in government schools in Victoria is down to just three percent. In parks, walkers and joggers dutifully arc around each other like passing ships.”

Glover acknowledged that certainly, there were voices attacking the government’s response as excessive.

“Fittingly – given the topsy-turvy politics of Covid-19 – the Prime Minister’s main critics are populist right-wingers from his own side of politics, such as the radio host Alan Jones and the columnist Andrew Bolt. Australia’s very success in limiting infections is now being presented by Bolt as proof the threat was wildly exaggerated.”

The left is not always right, and the right is not always wrong, as the saying goes, and the left’s embrace of authoritarian measures and the destruction of civil liberties under the cloak of Covid would ultimately do them and the nation great harm.

But Glover was not of that view: “At the moment, the prime minister is winning the argument. The lockdown, however onerous, is working. Listening to experts is working. And working together, across political parties, is working.

“Will this new attitude outlive the pandemic? Probably not. But right now, the Australian and New Zealand ‘bubble’ looks like a pretty good place to be.”

Alex could hardly have agreed less. Relying on “experts” depended entirely on which experts you chose. Then again he had never agreed much with Richard, even in the good old days when he was one of a new breed of super-cool whiz kids on the fusty, venerable old institution known as The Sydney Morning Herald. Well; at least not on what constituted a story.

He and Richard had been friendly for a time. As a News Editor his ideas were not always gritty, but often successful. A front page story picturing Bondi Beach crowded with the nubile flesh of the day, and with tags explaining why each of them wasn’t at work like the rest of the toiling masses, had the city talking for weeks.

At a newspaper reunion not long before he had said to Richard: “You know, the best thing about you as News Editor, there were worse to follow.”

Richard didn’t take the joke, looked if anything a little miffed, and soon enough was off mingling with the crowd, his crowd.

***

As for Old Alex, he could not believe the population’s gullibility; and submissiveness.

Many people would make the same observation in the coming months; that the single most frightening aspect of the times was not the virus, but people’s willingness to comply unquestioningly with a blizzard of government edicts.

“We are all going to just have to learn to do as we’re told,” a woman at a local pie shop in Hawk’s Nest said when he started to grizzle about the various restrictions.

None of it would last, or so Old Alex believed, retaining as he did a naive faith in the natural, healthy scepticism of Australians.

There were weeks of confusion, a series of contradictory government announcements which appeared almost deliberately designed to instill panic into the population. It seemed, in Alex’s fevered imagination at least, that there were many dark forces at play.

Meetings of more than two people had been banned. If you were standing outside your house speaking to a neighbour and a third person joined the group, you could be charged or arrested.

As far as Alex was concerned it was simply a version of martial law, introduced under the cover of Covid-19. There were so many stressors. The pubs were shut; he didn’t really know any other way to relax before returning to a dying parent he could not forsake. And so he would park the car by the lake in the wintering sky, and take a shot of bourbon out of a bottle in the boot. The houses were shuttered tight. There was no one around. It felt very lonely.

The trains were empty. The streets were empty. Support for the government, submissive acceptance of government fear mongering, compliance to what was effectively house arrest. How could it possibly be? You weren’t even permitted to engage in healthy activities like walking in a national park. The beaches were closed. Soon enough, at a local surfing spot, a sign went up: “If you’re from Sydney you’re not welcome.”

If you chose to go to your holiday house in the country to sit it all out, police would order you back to the city. How did that make sense?

Gifted Australian commentator Paul Collits was one of those quick out of the box. Governments weren’t that good at very much, he wrote, but they were good at lying to stay in office and at formulating strategies of self-protection.

In the age of Covid politicians were getting to appear to be heroes to voting populations cowed by fear, appearing presidential in the face of a largely manufactured crisis. Every leader on Earth was claiming to have saved their country. They couldn’t all be right. Even the bunglers and the dictators maintained strong public support.

“We now inhabit a strange world where politicians and health bureaucrats, working in tandem, run just about every element of our lives. This weird new system has replaced democracy as we once knew it, and it may not be over any time soon. We should all find this quite chilling. And sinister.

“The politicians of the Anglosphere are on to a good lurk during these Covid times, as are the public health officials having their fifteen minutes or so in the sun.

“The western world is in the grip of rule-by-health-official. These unelected titans provide endless cover for politicians. They have made numerous life-affecting decisions of dubious scientific authority under various emergency powers.”

The public only saw a banal surface. Everywhere leaked. The nightmare was just beginning.

Dean Sewell was awarded Australian Press Photographer of the Year in 1994 and 1998.

Sewell is represented by Charles Hewitt Gallery, and has work regularly exhibited in leading Australian and International galleries. He is a founding member of professional photographers collective Oculi.

John Stapleton is one of Australia’s most experienced general news reporters. Unfolding Catastrophe: Australia will be available in July of 2021. A collection of his journalism can be found here.