The photographer Anton Cermak was a legend of Sydney newspapers and it was a privilege to have worked with him.

https://www.smh.com.au/articles/2003/09/08/1062901994743.html

Anton Cermak, Photographer, 1933-2003

When Anton Cermak fled Prague in 1968 he gave the negatives of the photographs he had taken of the Russian invasion to his friend, who hid them in her brassiere. The couple headed for Vienna and the pictures were published around the world.

Cermak and the woman who was to become his wife, Jana, applied to Brazilian and Australian authorities for immigration papers. “We wanted to go as far from Europe as possible,” Jana Cermak said after her husband’s funeral.

The Australian papers turned up first. Australia would do, they agreed. Arriving in Sydney in January 1969, Cermak went to the Herald office and asked, as well as he could with his almost total lack of English, for a job.

He had no portfolio of photographs but he had the negatives of the action shots taken in Prague. John Rich, the pictorial manager, recognised the pictures. The refugee had a job.

He worked for the Herald and other Fairfax newspapers and won several awards, including one in the British Press Photographer of the Year competition.

Cermak was born in Prague. Although his first love was photography, his father was a businessman so he studied commerce. Anton’s opposition to the communist regime as a student landed him in jail in the 1950s.

The touch of rebellion about him did not end there. He was a footballer and a rower and hit on the idea of placing a camera inside the rowing shell in which he was competing, to take action shots by activating the camera with a foot. Officials disqualified the eight-man crew from a national competition.

Cermak welcomed the advent of Alexander Dubcek as first secretary of the Czechoslovak Communist Party and the reforms he brought in what became known as the Prague Spring of 1968. The Russians who dominated the then Soviet Bloc were less enthusiastic. They sent in the tanks, occupied the country and forced Dubcek to resign.

Cermak was one of only a handful of photographers who documented the first hours of the Russian invasion in 1968. The films were smuggled to the West.

He said afterwards of the picture of the tank crew on this page: “The officers did not like large crowds of people around their tanks. They did not like cameras, either. The best way to solve the problem was gun.”

He photographed young people protesting, some with flags, in front of tanks in Wenceslas Square. After two days of Russian occupation, he photographed invading soldiers reading copies of Pravda, the Russian newspaper whose title translates as “Truth”.

Cermak said later: “The paper explained to the troops where they were, why and what to do. Most of the soldiers did not know what was going on.”

Cermak had hidden his camera under a newspaper taken from a tank crew. After the soldiers saw the lens he, his camera and film survived a wild chase through Prague streets.

Jana was also a photographer and they married in Australia in 1972. While he worked in black and white, she worked in colour and usually in the dark room.

Soccer was a minor football code in Australia when they arrived and he made it one of his specialties. He went with the Australian team to Germany in 1974, the last time Australia contested World Cup finals. He had an affinity with coaches such as Rale Rasic and Frank Arok.

He also loved tennis. He formed friendships with visiting Czech players, including Ivan Lendl, Martina Navratilova and Hana Mandlikova, who sometimes stayed with Anton and Jana in their Bondi apartment.

His photographs of sporting matches and sports people appear in five book collections. He said of his work: “It was a hobby which became a career. I have never regretted a minute of it. It was love and hate. I loved the results, and sometimes hated the conditions.”

He was an emotional man who loved a party and a drink, usually vodka. He and Jana conducted memorable toga parties.

They also loved the Australian sun and fishing. They retired to Mackay and spent a good deal of time on Whitsunday islands, often as nudists. Anton built a fishing shack on a headland at Proserpine.

He even developed a neat, though somewhat crude, sense of Australian irony. Asked how he was of a morning, he would sometimes say: “I look out my window, sky is blue, sun is shining, birds are singing. C— of day.”

Anton and Jana both lost contact with their families after leaving Czechoslovakia. Jana never saw her mother again. Anton met a sister during his time at the 1974 World Cup. But after planning a post-retirement European holiday of six weeks in 1992, he and Jana flew home to sunny Australia after 10 days.

Cermak’s farewell from journalism was attended by the then NSW premier, Nick Greiner. The two had something in common. Greiner’s Hungarian family had suffered at the hands of the Nazis during the war and the communists after it. Together they applauded Australian multi- culturalism.

Tony Stephens

PHOTOCOPY

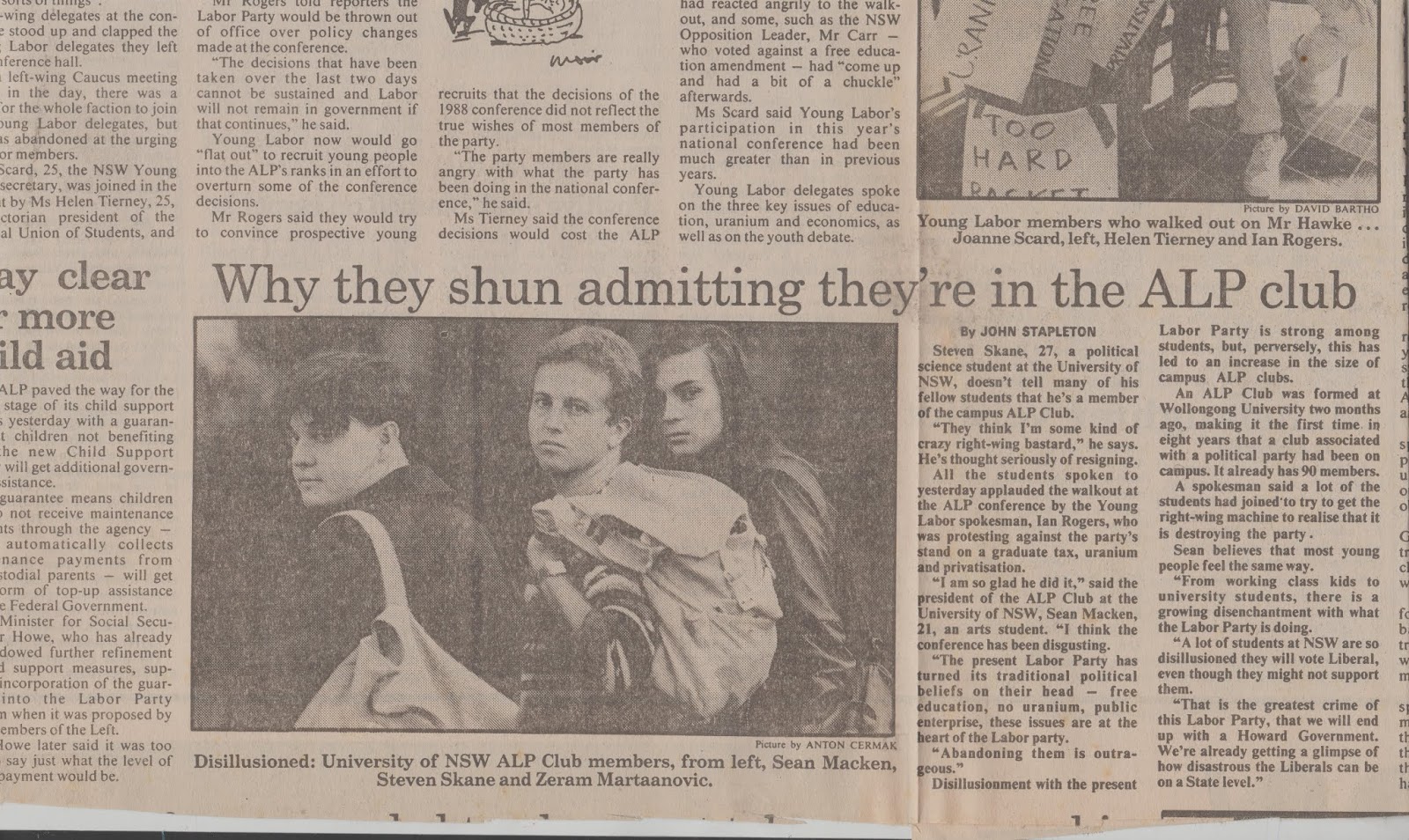

ActivePaper ArchiveSydney Morning Herald, 9/06/1988